What are Lewis Dot Structures

As mentioned in the “Formal Charge” topic, Lewis Dots are a 2D representation of a molecule’s structure. We can visualize the arrangement of electrons around each atom, as well as the covalent bonds between them.

Note that we only draw Lewis Dot diagrams for molecular compounds and polyatomic ions.

Here are some examples ↴

Bonds: Covalent bonds are represented by lines. Each line represents two shared electrons. If you see two lines between two atoms, that is called a double bond (4 shared electrons). Three lines indicates a triple bond (6 shared electrons). However, there is no such thing as a quadruple bond (atoms would never need to share 8 electrons).

Non-Bonding Electrons: Electrons that do not participate in bonding are represented by dots. Most of the time, non-bonding electrons exist in pairs. A pair of nonbonding electrons is called a lone pair.

We will often refer to the non-bonding electrons as “dots”.

How to Draw Them – Neutral Molecule

The key to being good at Lewis Dots is practice. We urge you to spend time trying to draw different molecules. This allows you to figure out common patterns, learn from mistakes, find exceptions, and improve your speed. Eventually, you won’t even have to think about how to draw them. It will just come naturally.

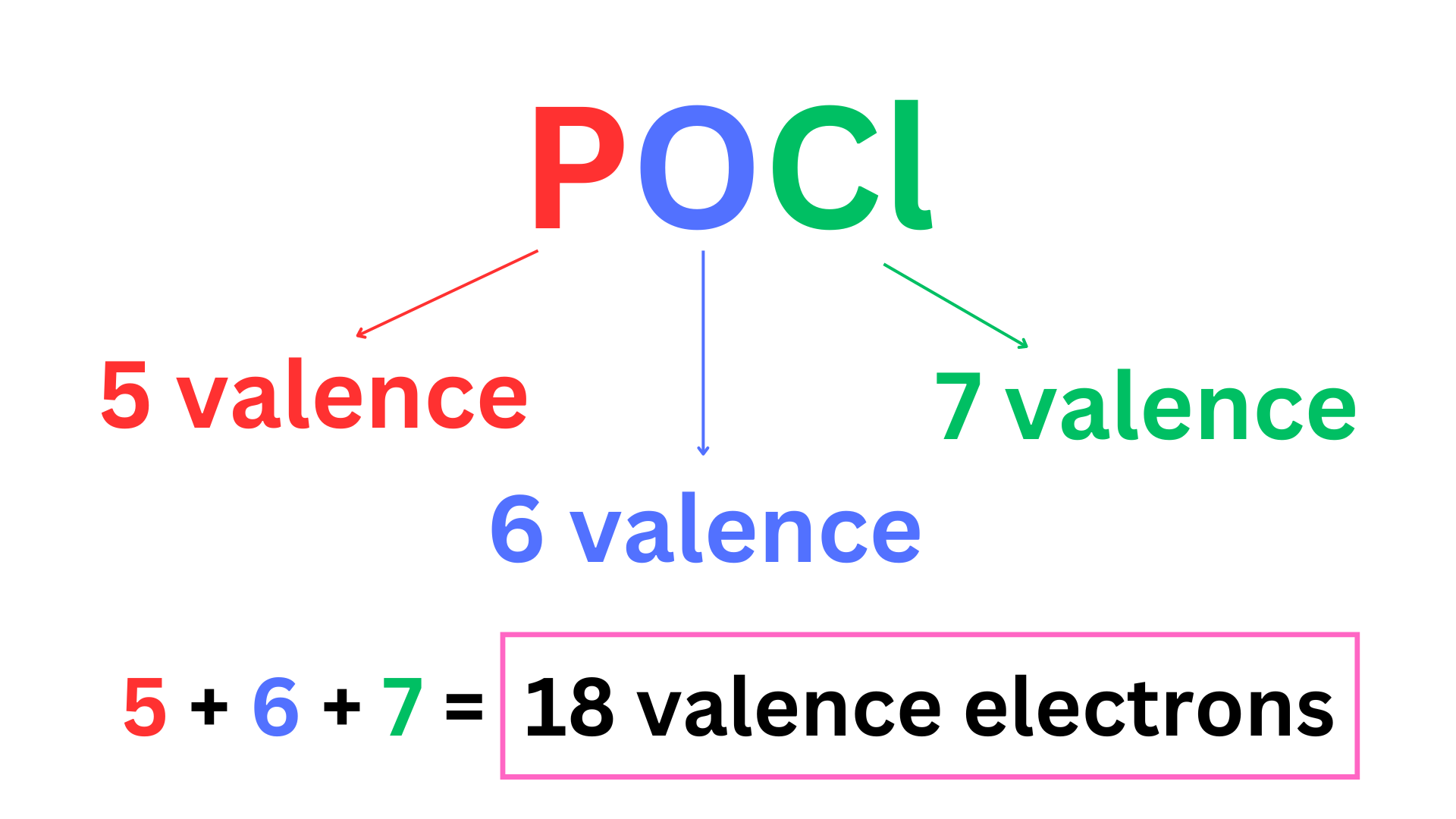

There are many different methods for drawing Lewis Dot diagrams. This is the way that we found to be the easiest. We will explain while running through an example, using the imaginary molecule POCl. If the instructions ever become confusing, the example should provide clarity ↴

Step 1: Count the total number of valence electrons.

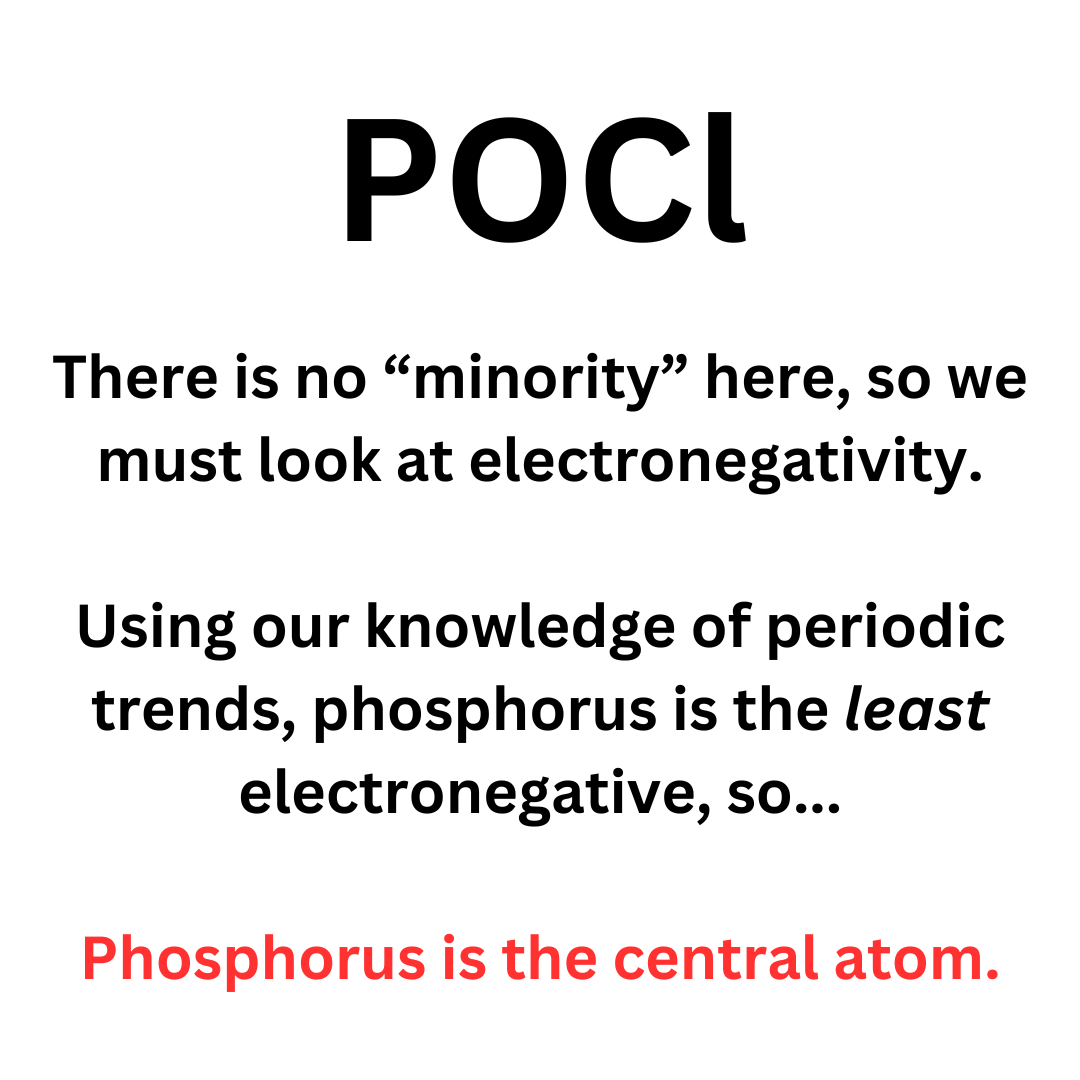

Step 2: Determine the central atom (the atom in the center of the molecule that is bonded to all of the other atoms).

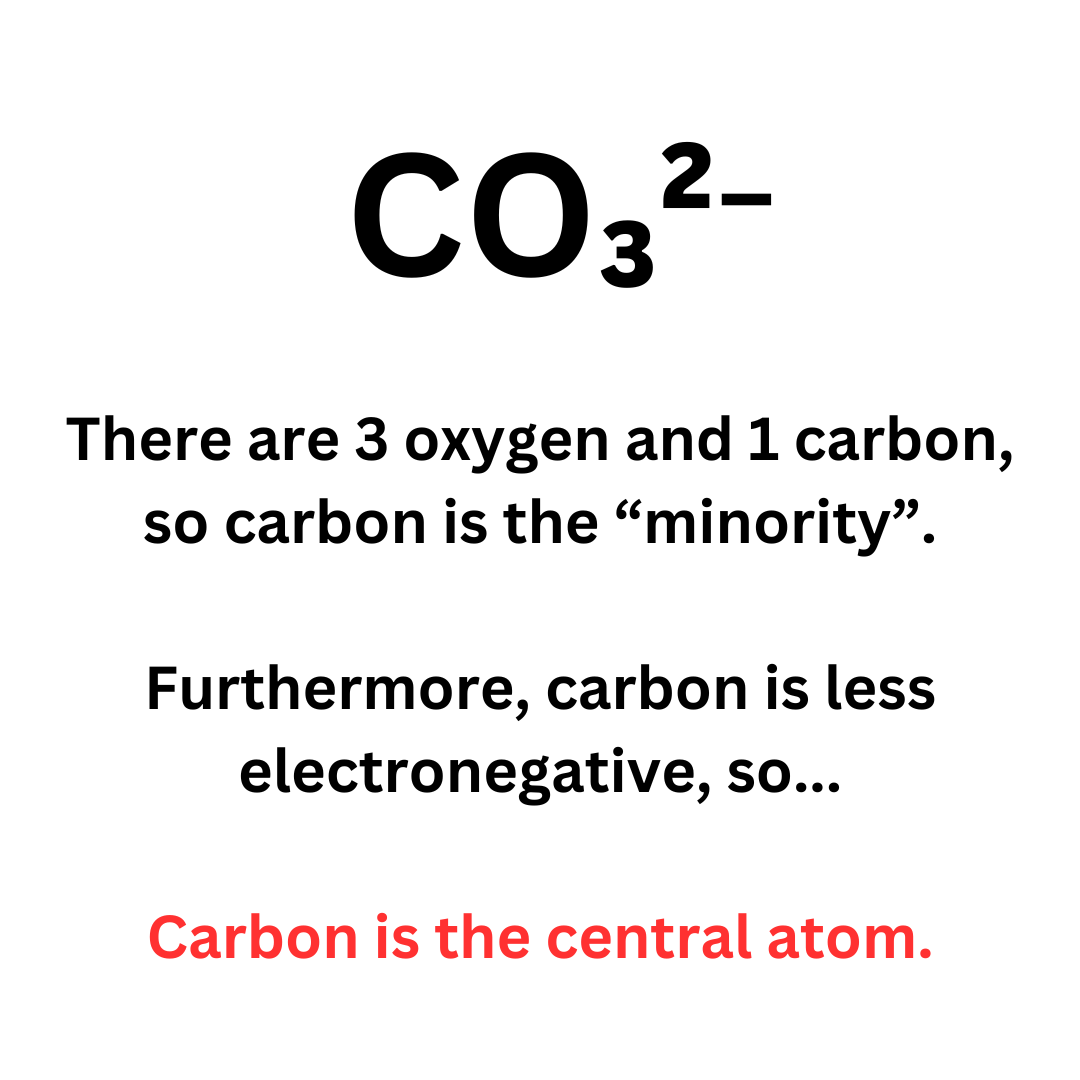

The central atom is typically the least electronegative element, or the element that is able to form the most bonds.

Or, in molecules like ClO₄⁻, where there is a lot more of one element than the other, pick the “minority”. In ClO₄⁻, there is only one chlorine while there are four oxygen, so chlorine is the central atom.

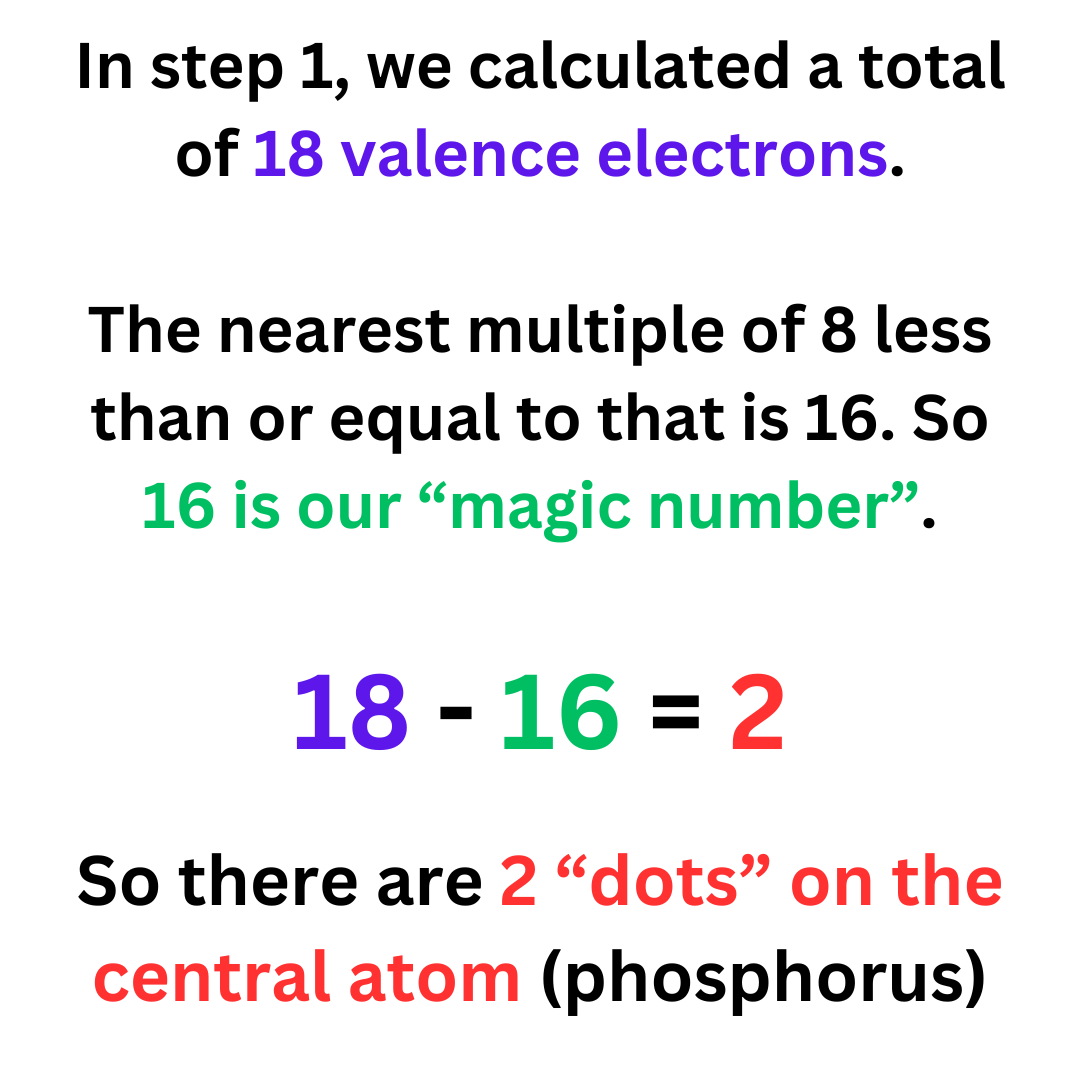

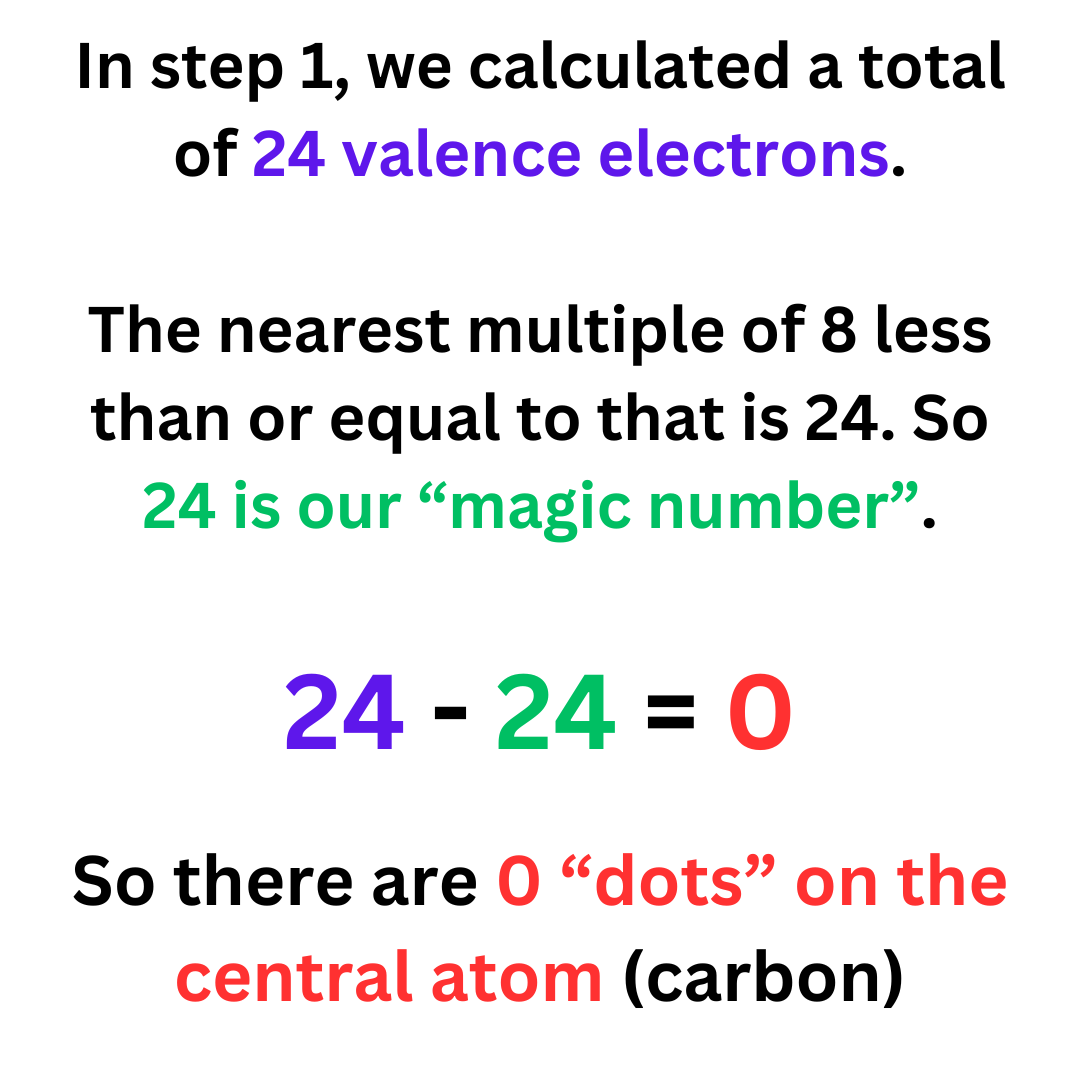

Step 3: Find the number of “dots” on the central atom (remember that dots represent nonbonding electrons).

Note that this step does not work if there is any hydrogen in the molecule. If there are, skip to step 5.

To do this, find the nearest multiple of 8 that is less than or equal to the total number of valence electrons (that you calculated in step 1). We’ll call this the “magic number”.

Dots on central atom = Total # V.E. – magic number

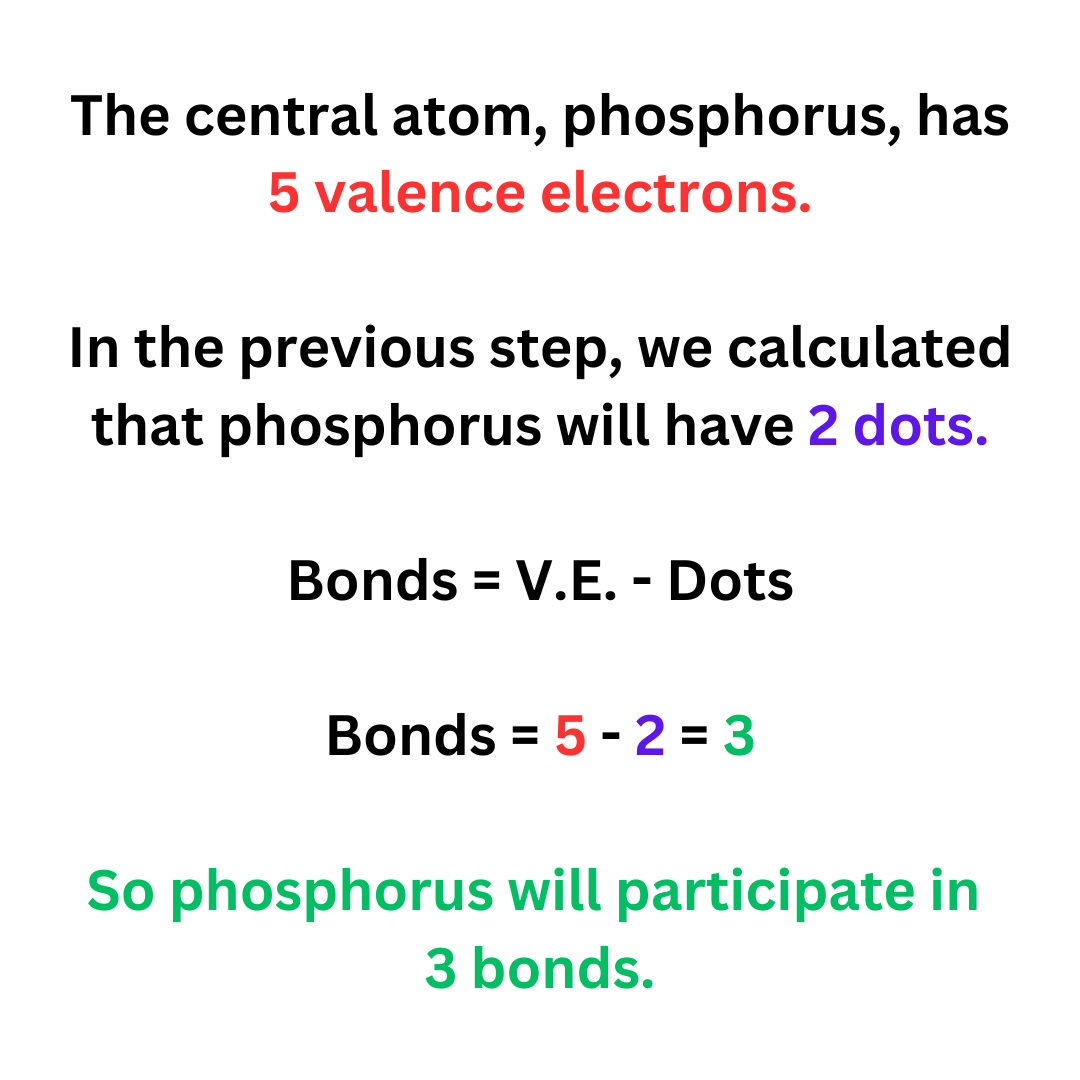

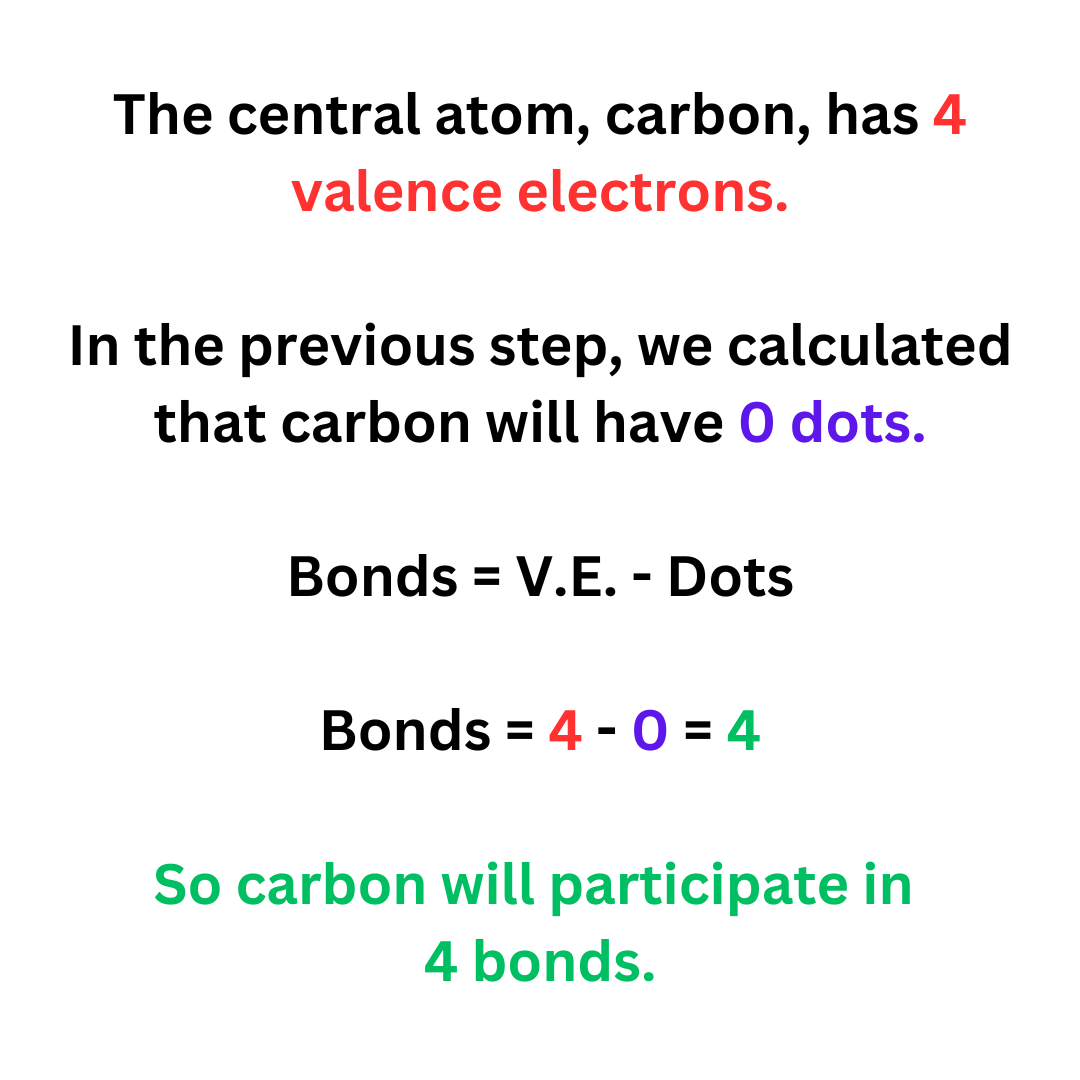

Step 4: Calculate number of bonds on the central atom.

Note that this step does not work if there is any hydrogen in the molecule. If there are, skip to step 5.

Recall how to calculate formal charge ↴

F.C. = V.E. – (Bonds + Dots)

In most cases, the central atom will have a formal charge of 0. (Positive polyatomic ions are an exception).

Assuming that F.C. = 0 for the central atom, we get the expression ↴

0 = V.E. – (Bonds + Dots)

Rearranging the equation to isolate Bonds, we end up with ↴

Bonds = V.E. – Dots

You know the number of valence electrons that the central atom has. In step 3 we found the dots on the central atom. So, you can calculate the number of bonds on the central atom.

Step 5: Using what you know, draw the molecule.

If you had to skip steps 3 and 4 (due to hydrogen), this will be a little bit more difficult because you have less information to work with.

First, draw out what you know: the atoms, the central atom, and dots on the central atom.

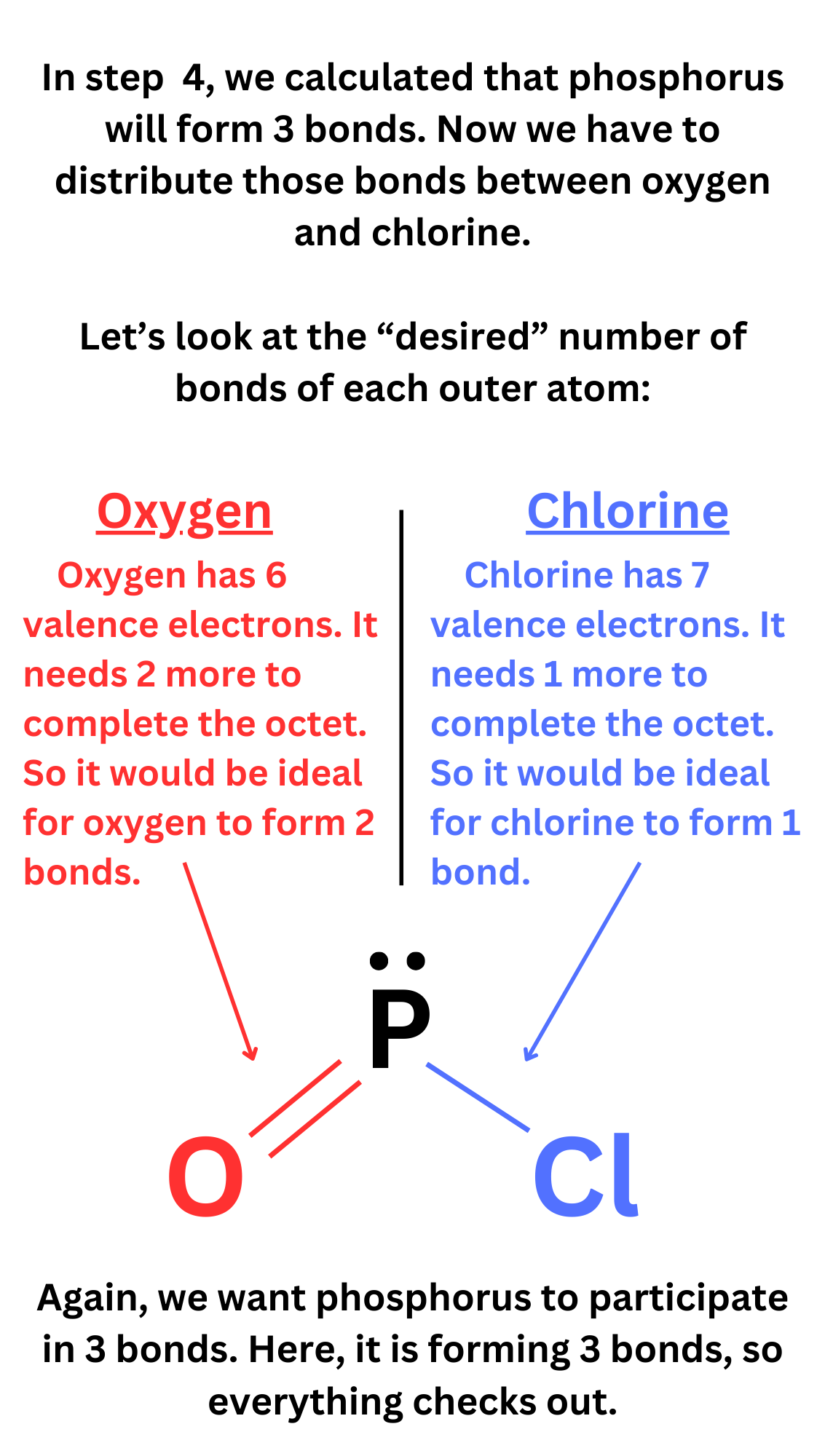

Now, you have to decide how to distribute the bonds of the central atom. We determined how many bonds the central atom participates in, but how do we distribute these bonds between the outer atoms?

Outer atoms will typically form the number of bonds needed to complete the octet.

Ex. Oxygen has 6 valence electrons. It needs 2 more electrons to have 8. So outer oxygen atoms typically form 2 bonds.

Ex. Nitrogen has 5 valence electrons. It needs 3 more electrons to have 8. So outer nitrogen atoms typically form 3 bonds.

Ex. Bromine has 7 valence electrons. It needs 1 more electron to have 8. So outer bromine atoms typically form 1 bond.

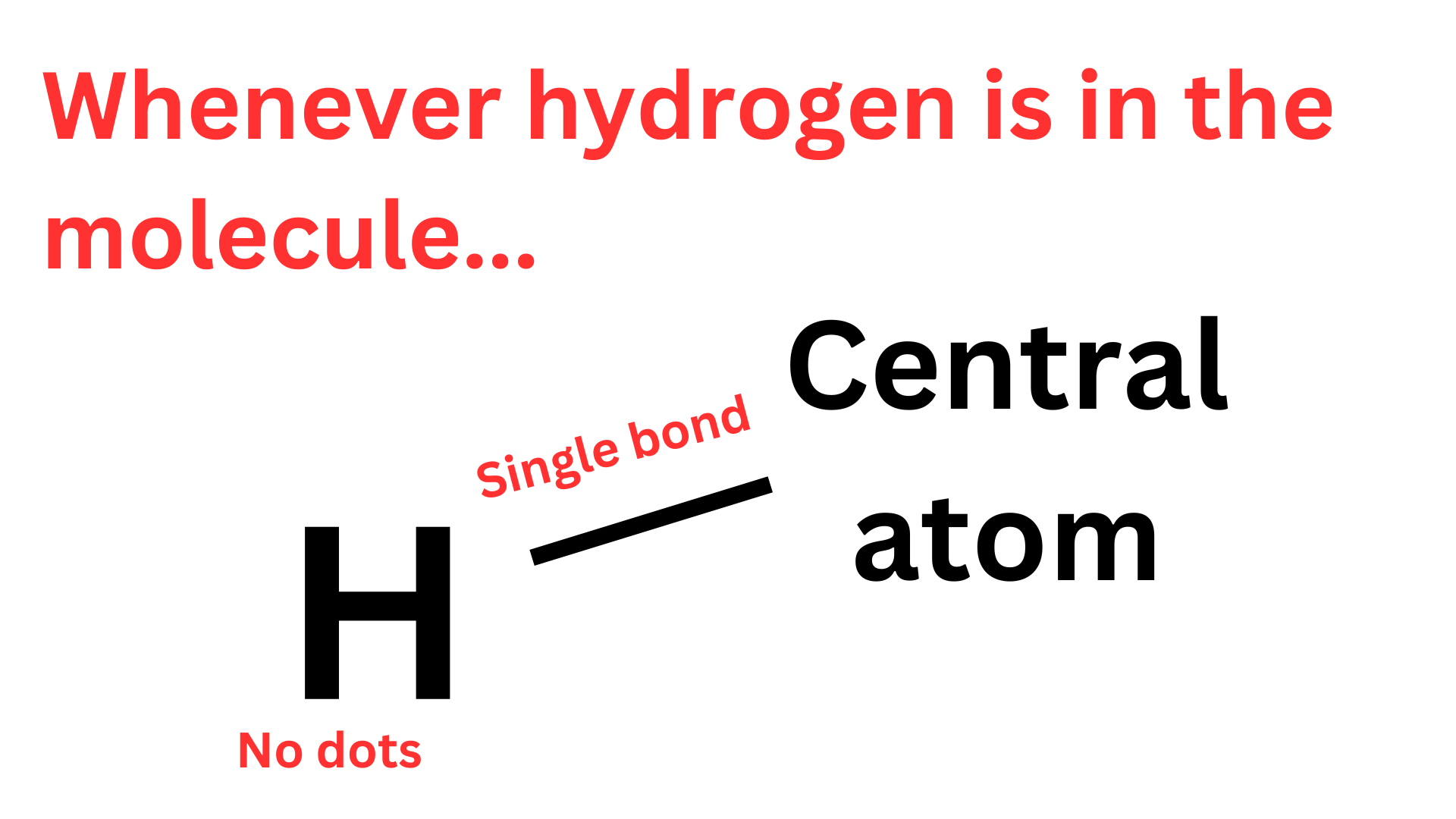

As aforementioned, hydrogen invalidates step 3 & 4, which is annoying, but hydrogen atoms themselves are very easy to deal with. Hydrogen only needs 2 valence electrons, so it will always form exactly 1 covalent bond with the central atom. The hydrogen’s only electron is a part of that covalent bond, so hydrogen atoms never have lone pair electrons (dots).

Therefore, if a compound contains hydrogen, it will have a single bond with the central atom, and no dots.

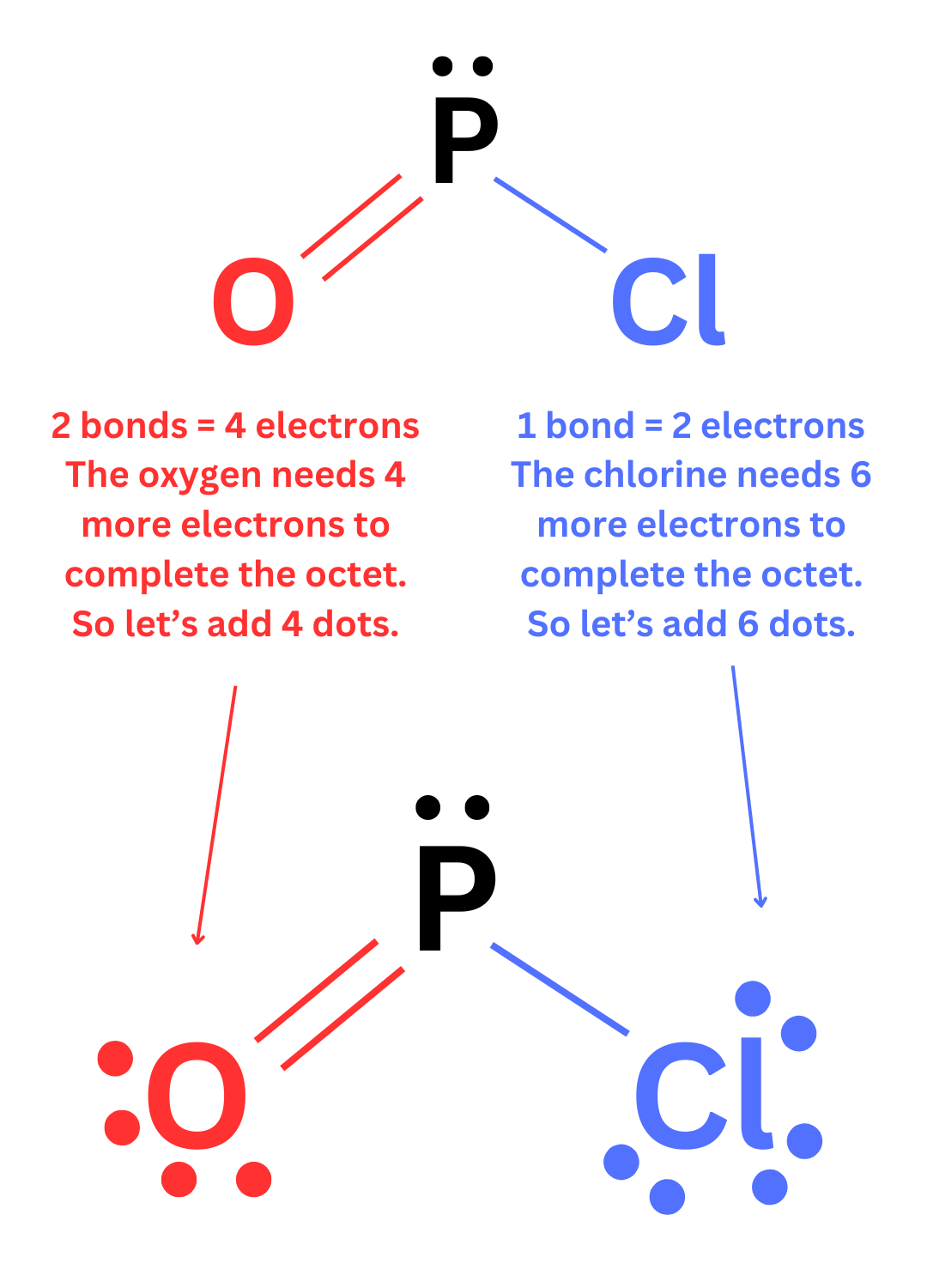

Once you have drawn the bonds on each atom, you are almost finished. The last step is to complete the octets by adding lone pairs. Count the number of bonds on each atom. Each bond holds two electrons. Determine how many more electrons the atom needs in order to have 8. Then add those remaining electrons as lone pairs (dots).

Step 6: Double check your work.

First, double check that each atom has a complete octet (8 valence electrons). Remember that each bond counts as 2 electrons, and each dot counts as 1.

There are two cases where you can ignore the octet rule ↴

1. Boron: Boron only needs 6 valence electrons to become stable.

2. Central Atom: Often, the central atom is allowed to have more than 8 valence electrons (but not less). We call this an expanded octet. You will learn more about this in the next unit “Chemical Bonding.”

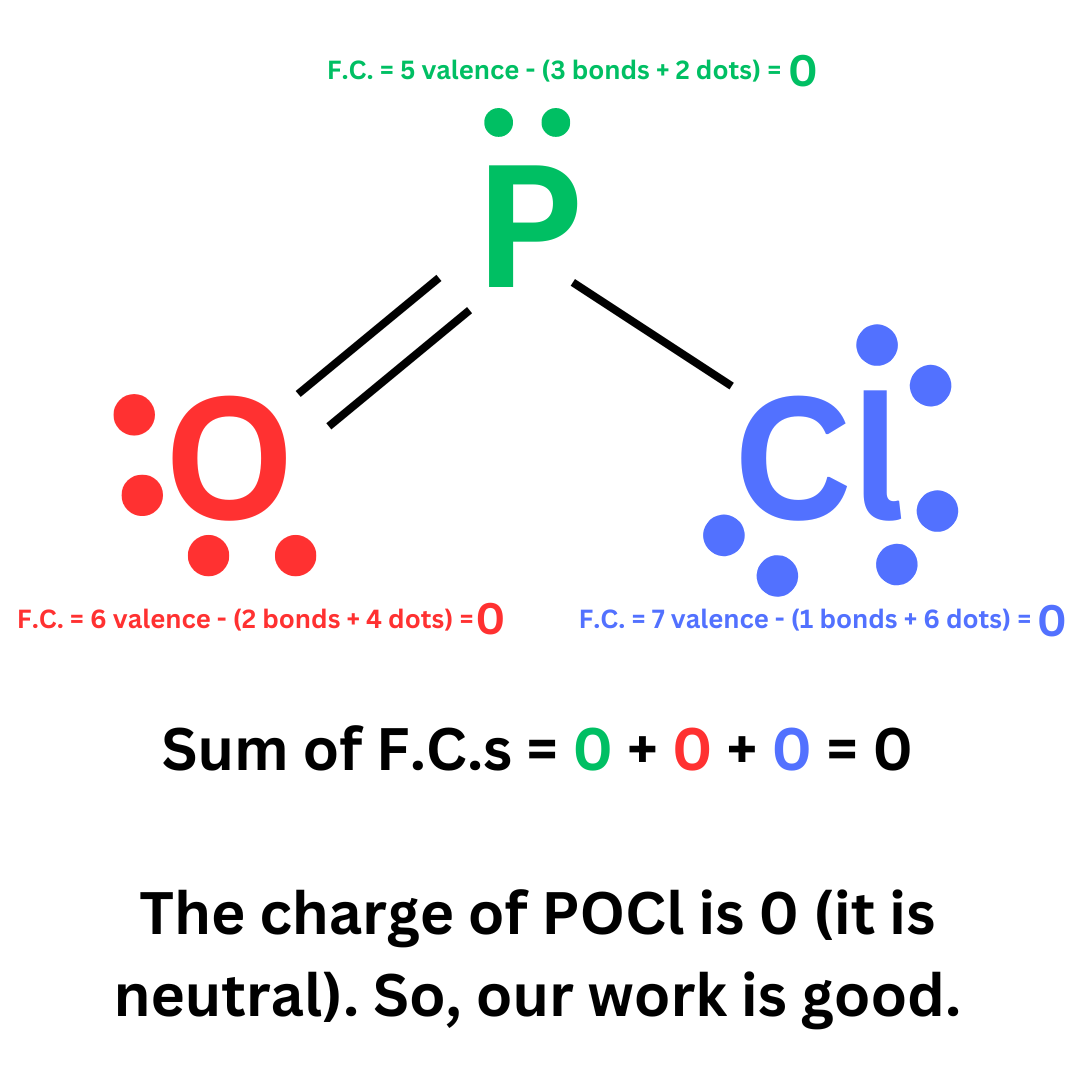

Finally, double check the formal charges. Remember that the sum of the formal charges of individual atoms must be equal to the overall charge of the molecule.

How to Draw Them – Polyatomic Ion

Even though polyatomic ions are “ions,” they are still composed of atoms covalently bonded together. Thus, we can draw them using Lewis Dot diagrams.

When dealing with polyatomic ions, most steps are exactly the same as they were for drawing neutral molecules, but some will be slightly different.

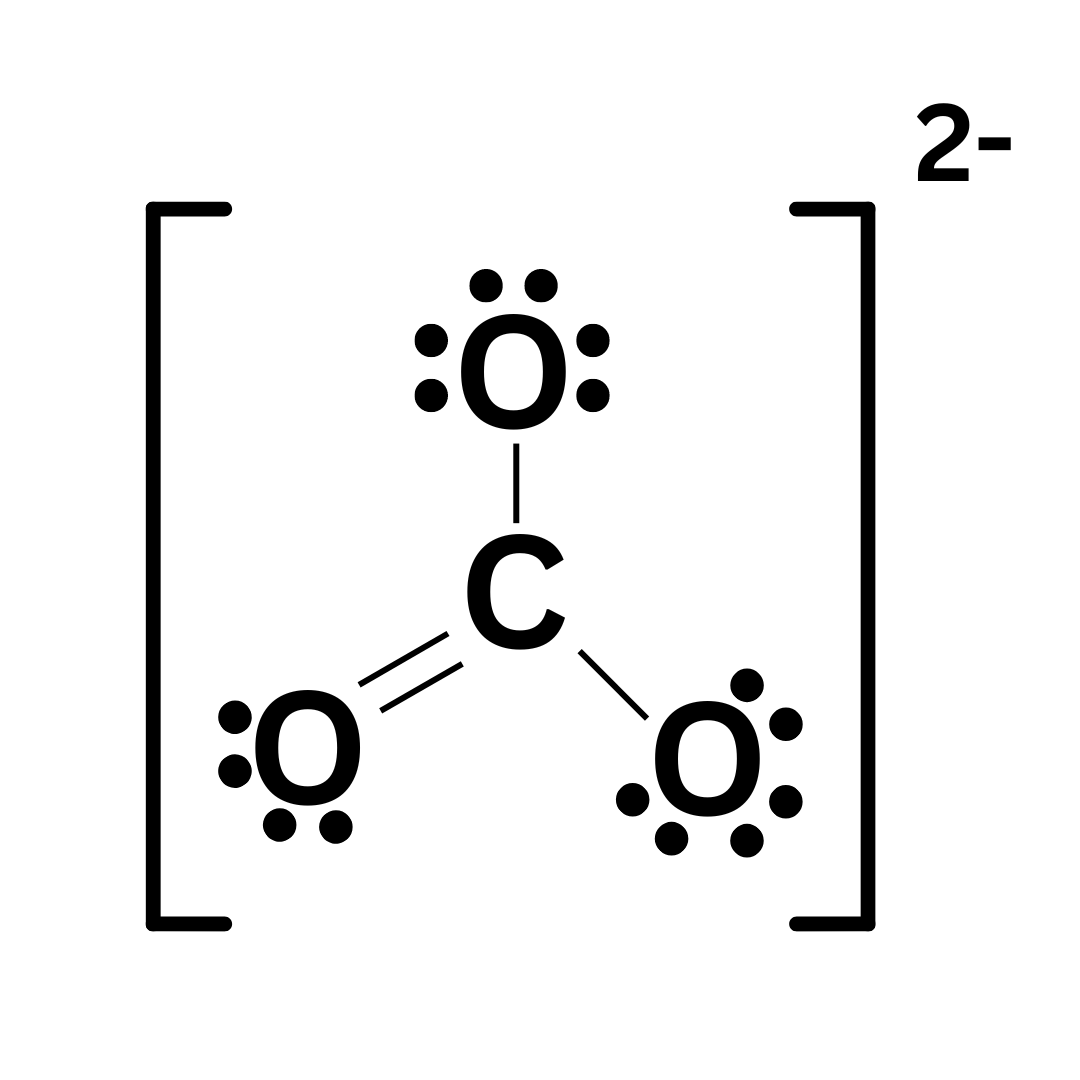

We will run through this using the polyatomic ion CO₃²⁻ ↴

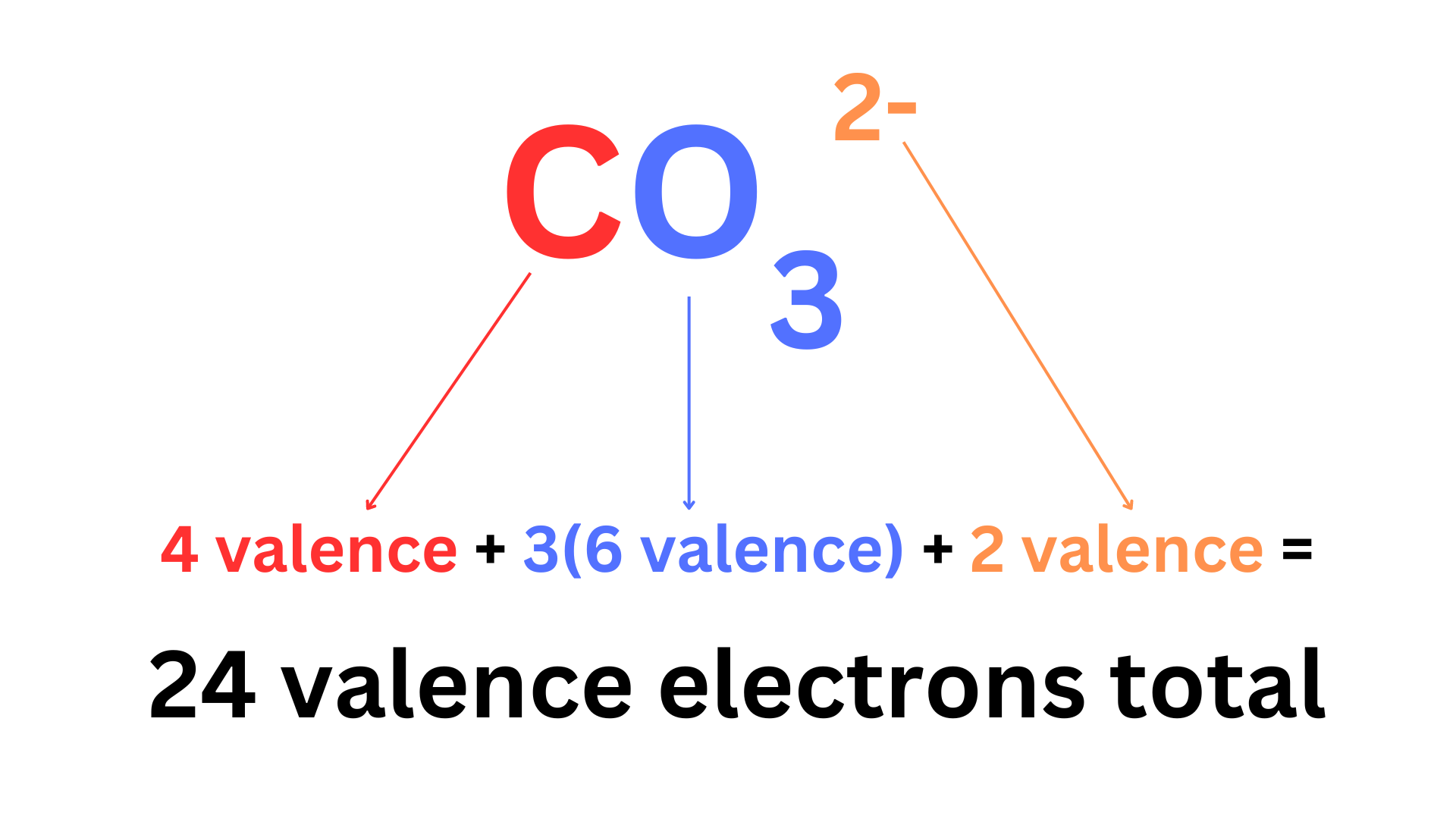

Step 1: Count the total number of valence electrons.

This step is slightly different for polyatomic ions. You must account for the charge.

For anions, you need to add the amount of electrons indicated by the charge. For cations, you need to subtract the amount of electrons indicated by the charge.

Ex. NH₄⁺ has 9 valence electrons. However, since it is a cation, we must remove electrons. The charge is 1+, so we subtract 1 electron. Our total is now 8.

Ex. SO₄²⁻ has 30 valence electrons. However, it is an anion, so we must add electrons. The charge is 2-, so we add 2 electrons, bringing our total to 32.

Step 2: Determine the central atom. This is the exact same as it is for neutral molecules.

Step 3: Find the number of “dots” on the central atom. (This is the same as it is for neutral molecules.)

Step 4: Calculate number of bonds on the central atom. (This is the same as it is for neutral molecules.)

Step 5: Using what you know, draw the molecule.

This uses the same logic that is used for neutral molecules. We still need to distribute the bonds between the outer atoms. We also need to look at how many bonds an atom “desires” to form.

The only difference is that we don’t want all of the atoms to have a formal charge of zero. So, you need to mess around with the structure a little bit, trying to distribute the bonds so that the formal charges add up to the charge of the overall molecule.

You can manipulate the formal charge of certain atoms by changing the number of bonds that they have. (Remember, F.C. = V.E. – (Bonds + Dots).)

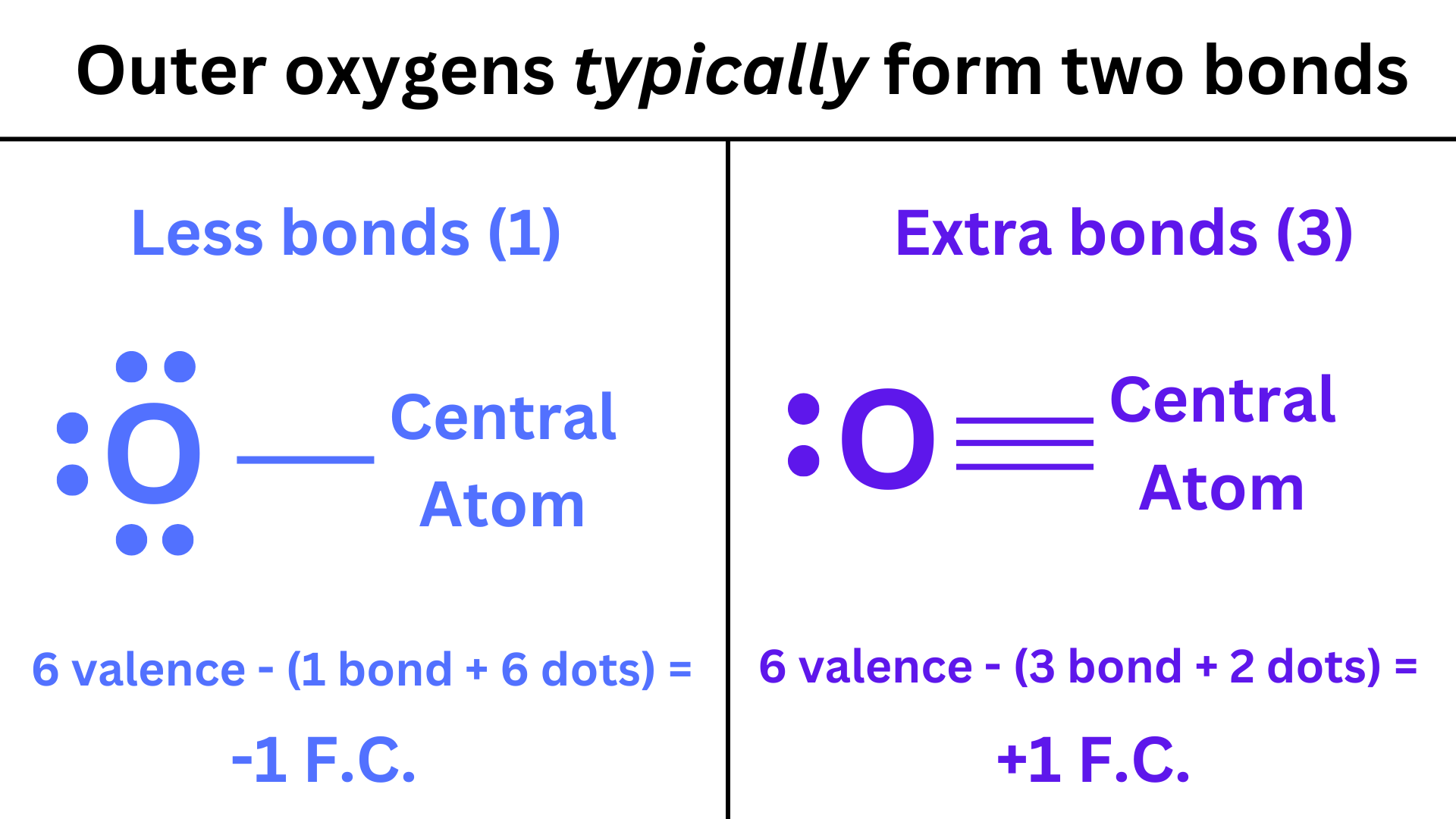

Ex. Oxygen typically will form 2 bonds when it is an outer atom (because it needs 2 valence electrons to complete the octet). This gives you an oxygen atom with a formal charge of zero. However, if we only give oxygen 1 bond, it will have a negative formal charge.

On the other hand if we give oxygen an extra bond (3 bonds total), it will have a positive formal charge.

Giving an outer atom an extra bond will give it a positive formal charge. Giving an outer atom less bonds will give it a negative formal charge. (This is not true for the central atom.)

Keeping that in mind, find a way to distribute the central atom’s bonds in a way that results in the desired formal charge.

Finally, complete the octet by adding lone pairs.

Step 6: Add brackets and indicate the charge.

This step is unique to polyatomic ions. You must put square brackets around the entire molecule, and write the charge of the ion.

Step 7: Double check your work.

Make sure that all octets are complete and that the formal charges make sense.

Hydrogen Example

As we mentioned, molecules containing hydrogen can be more difficult to draw, because you have to skip step 3 and 4. So, we wanted to run through an example of a molecule containing hydrogen: CH₂Cl₂.

We still need to determine our central atom. In this case, it will be carbon. Hydrogen can never be the central atom because it can only form one bond. Carbon is less electronegative than chlorine, so it is the central atom. Also, carbon is the “minority” in this case.

Now we go straight to drawing the molecule. Although we don’t know how many bonds carbon will form, or how many lone pairs it will have, hydrogen does provide one advantage: it will always form one bond with the central atom and have no lone pairs ↴

Now, let’s look at chlorine. Chlorine has 7 valence electrons, meaning it only needs 1 more electron to reach stability. Thus, chlorine will likely form 1 bond with carbon ↴

Let’s look back to the central atom, and make sure that this makes sense so far. When we calculate the formal charge of carbon:

F.C. = 4 valence – (4 bonds + 0 dots) = 0

The central carbon has a formal charge of 0, which is a good sign. If it didn’t, we would look to add lone pairs (“dots”).

Finally, we complete the octet by adding lone pairs ↴