Ionic Bonds

As you should know by now, ionic bonds exist between a metal and nonmetal. As a refresher, the highly electronegative nonmetal completely takes electron(s) from the metal. The nonmetal becomes an anion, and the metal becomes a cation. These two oppositely charged ions are attracted to each other to form an ionic compound.

Ionic compounds have an ordered lattice structure.

Lattice Energy: The amount of energy required to separate (break) a mole of an ionic compound. It is measured in kJ/mol.

The stronger the force of attraction between the metal and nonmetal, the more energy required to separate them. Thus, a stronger force of attraction results in a higher lattice energy.

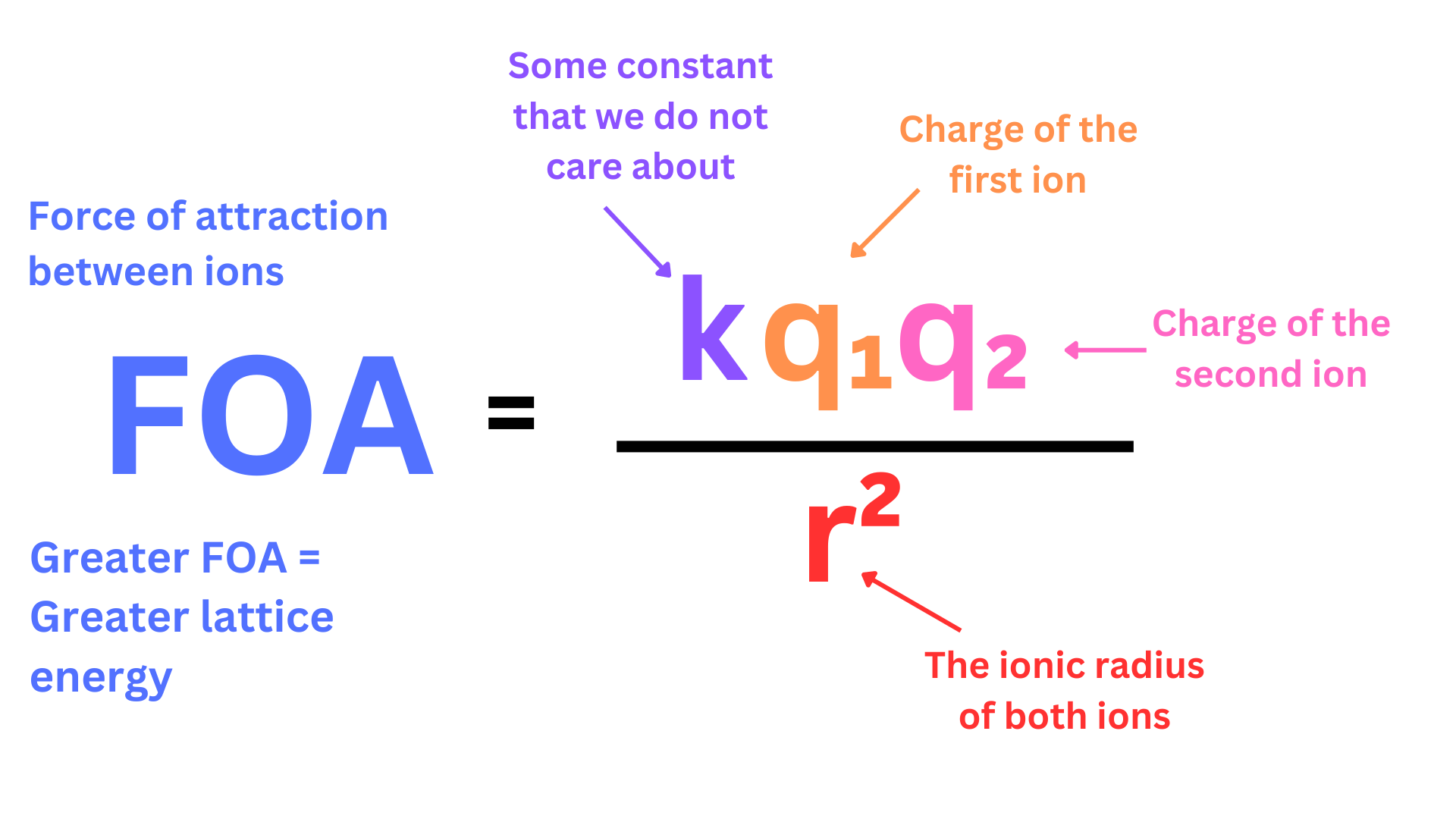

But how do we measure this force of attraction? We can use Coulomb’s Law (this law will pop up in many later units so understand it well).

Coulomb’s Law: The force of attraction between two charged particles is proportional to their charges and inversely proportional to their radius (remember that a greater force of attraction results in a higher lattice energy).

That sounds wordy and confusing, so just look at the equation ↴

As you can see, force of attraction increases as charge increases, and it decreases as radius increases.

You will never actually be asked to actually calculate FOA’s (forces of attraction) using Coulomb’s Law. However, you will need to compare FOA’s using the ideas of Coulomb’s Law. You need to remember that FOA increases as charge (of the ions) increases, and FOA decreases as ionic radius increases.

Think of a magnet. The FOA between the magnet and a piece of metal will increase with a stronger magnet (similar to increasing the charge of the ions). It will decrease as you move the magnet further from the piece of metal (similar to increasing atomic radius).

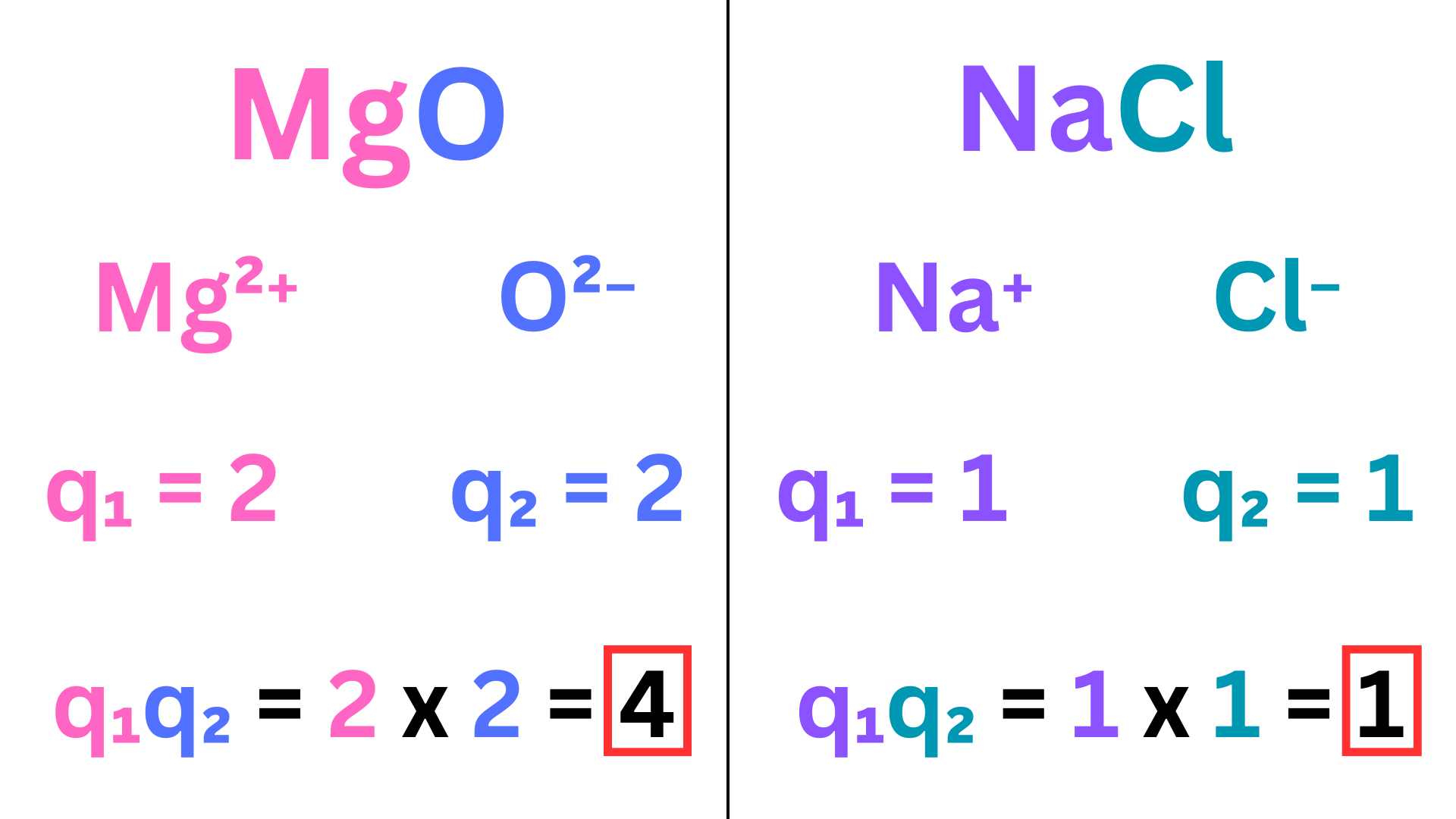

Let’s do an example: compare the lattice energy of NaCl and MgO. We will use Coulomb’s Law to compare the forces of attraction between the two ionic compounds.

Charge takes priority over radius. First, look at the charges of the ionic compounds. Multiply the charges of their ions. If there is a difference, you don’t even need to look at radius because the charge is more important. However, if the products of the charges are the same, then you must consider the radii.

Let’s look at the charges of MgO and NaCl ↴

The charges of MgO multiply to 4, while those of NaCl multiply to 1. So, we don’t even need to look at the ionic radii of these compounds. There is a greater force of attraction between the ions of MgO, so it requires more energy to separate them. This means that MgO has a greater lattice energy.

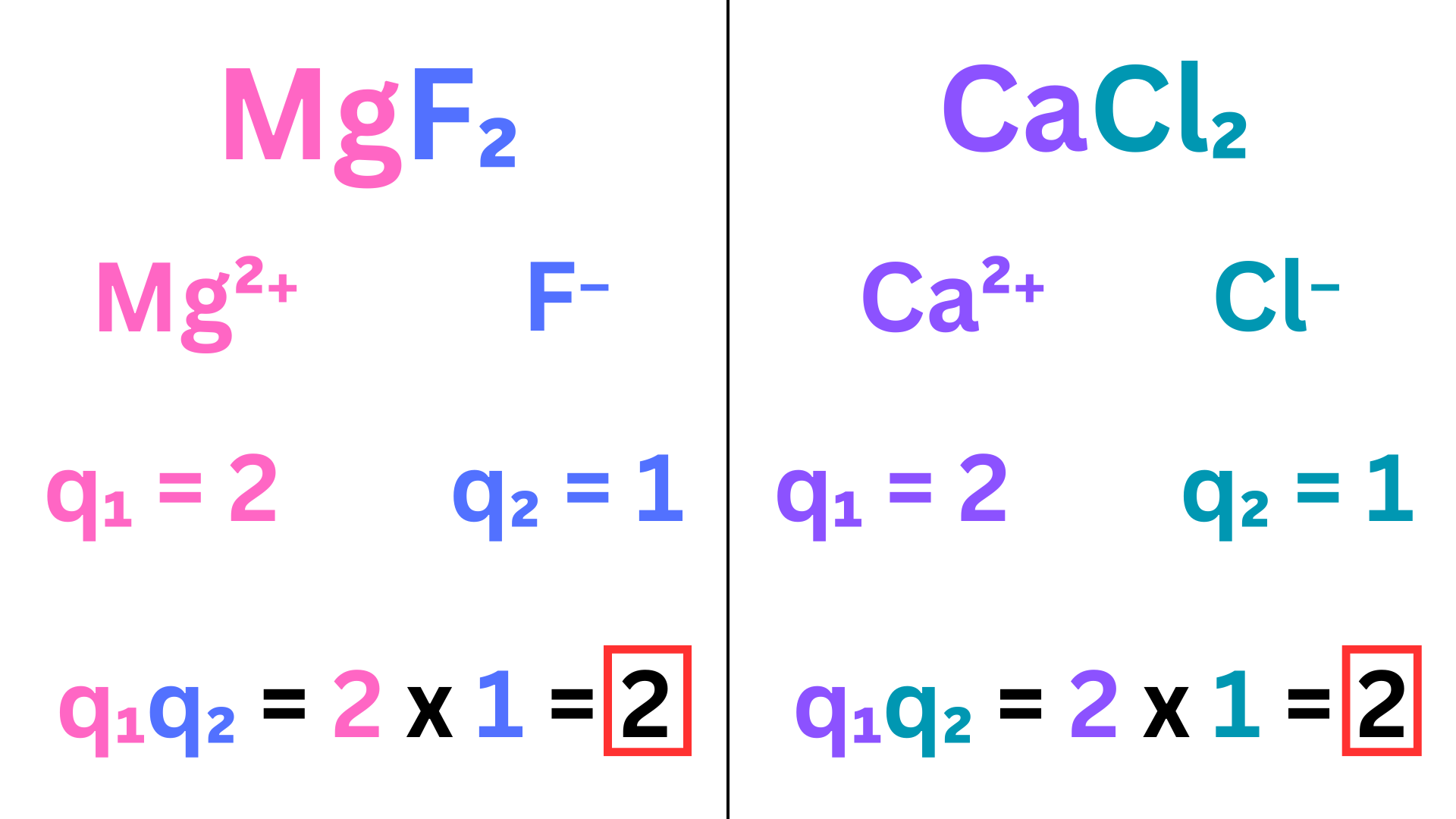

Let’s do another example, where radius does matter: compare the lattice energy of MgF₂ and CaCl₂.

We first compare the charges ↴

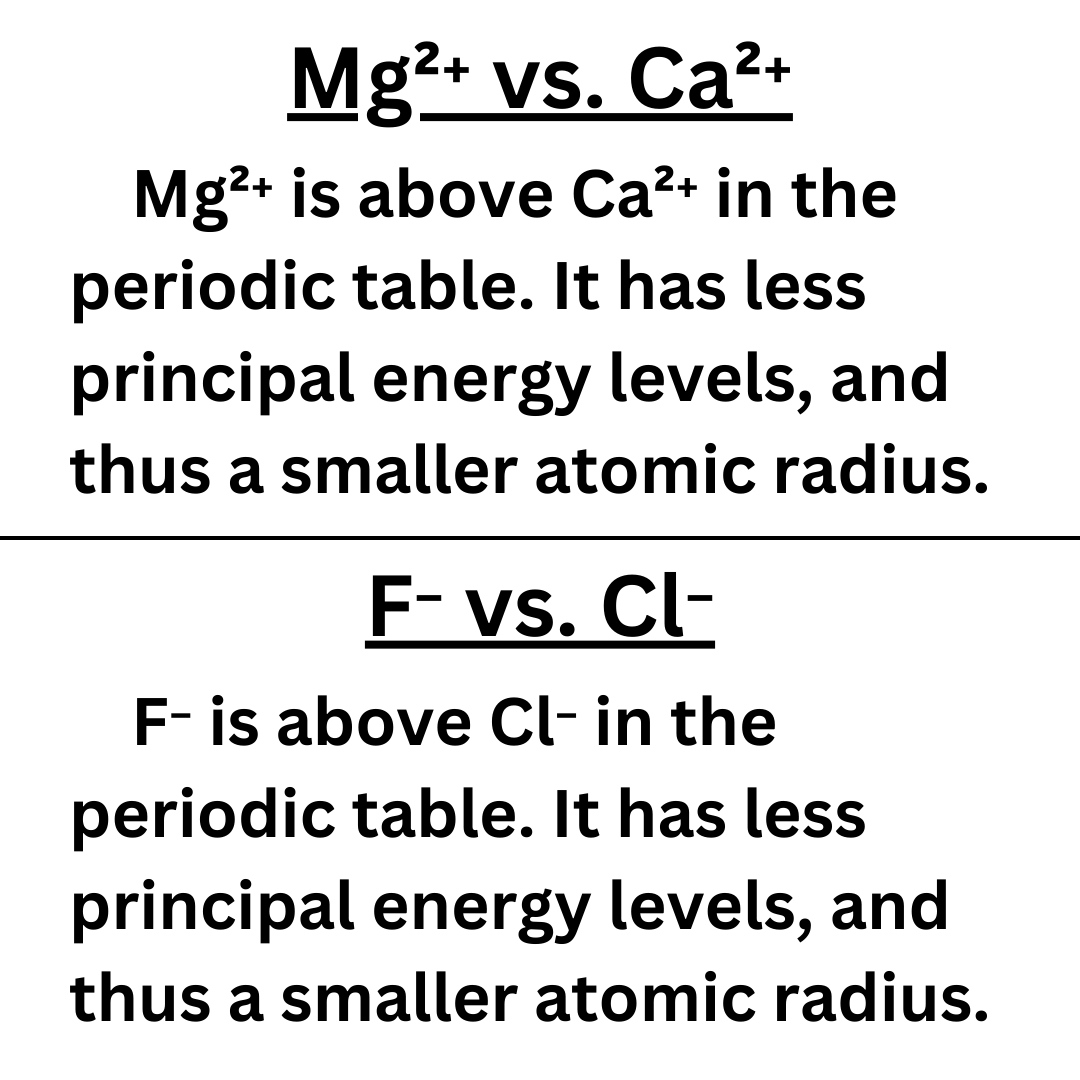

The products of the charges are equal, so we must now look at radius. Using your knowledge of periodic trends, compare the radius of the two anions. Then separately compare the radius of the two cations. The ionic compound with the smaller radii has the greater FOA.

Mg²⁺ is smaller than Ca²⁺, and F⁻ is smaller than Cl⁻. MgF₂ has a smaller radius, so it has a greater FOA between ions and, therefore, a greater lattice energy than CaCl₂.

Covalent Bonds

You should be very experienced with covalent bonds after learning about Lewis Dot structures. As a quick refresher, covalent bonds occur between two nonmetals. Electrons are shared between two neutral atoms. As you saw in Lewis Dots, atoms can form single, double, and triple covalent bonds.

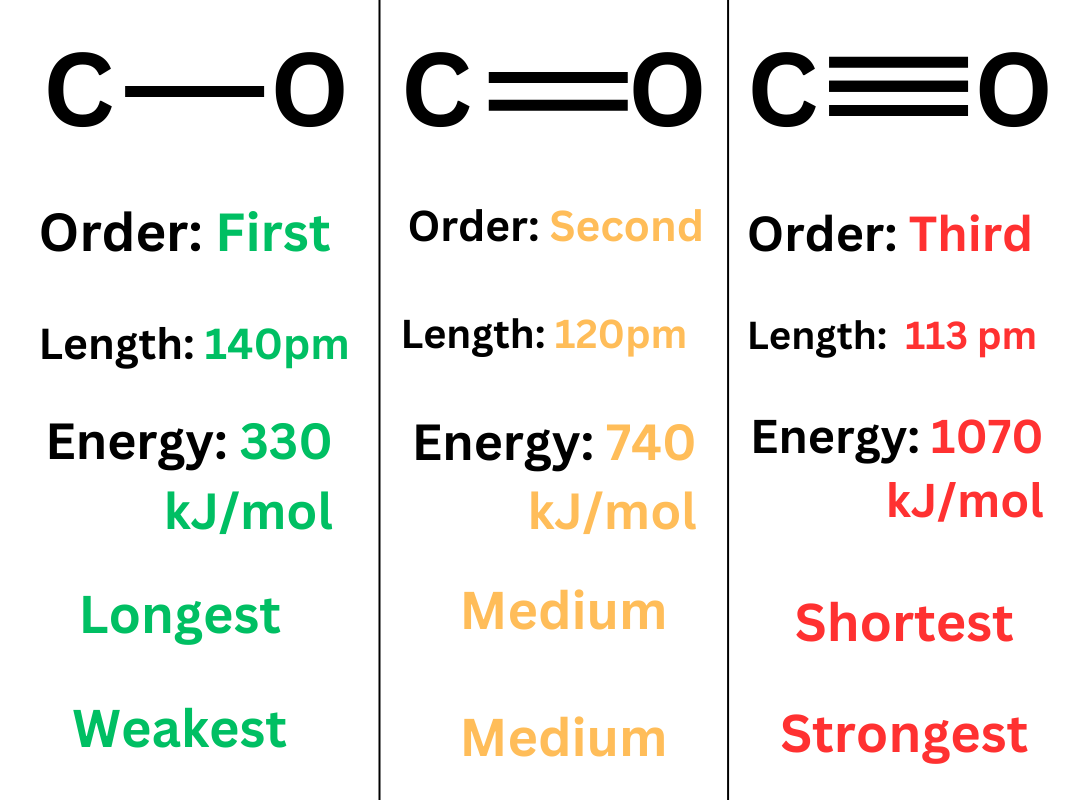

Bond Energy: The amount of energy required to break a mole of a certain covalent bond. It is measured in kJ/mol. Stronger bonds are harder to break, and therefore have a greater bond energy.

Ex. The S-F bond energy is 327 kJ/mol. To break one mole of covalent bonds between sulfur and fluorine, it would take 327 kJ.

Bond Length: The distance between two covalently bonded atoms. This is often measured in picometers (pm).

Bond length is inversely proportional to bond strength. This means that longer bonds are weaker (lower bond energy & easier to break). Shorter bonds are stronger (higher bond energy & more difficult to break).

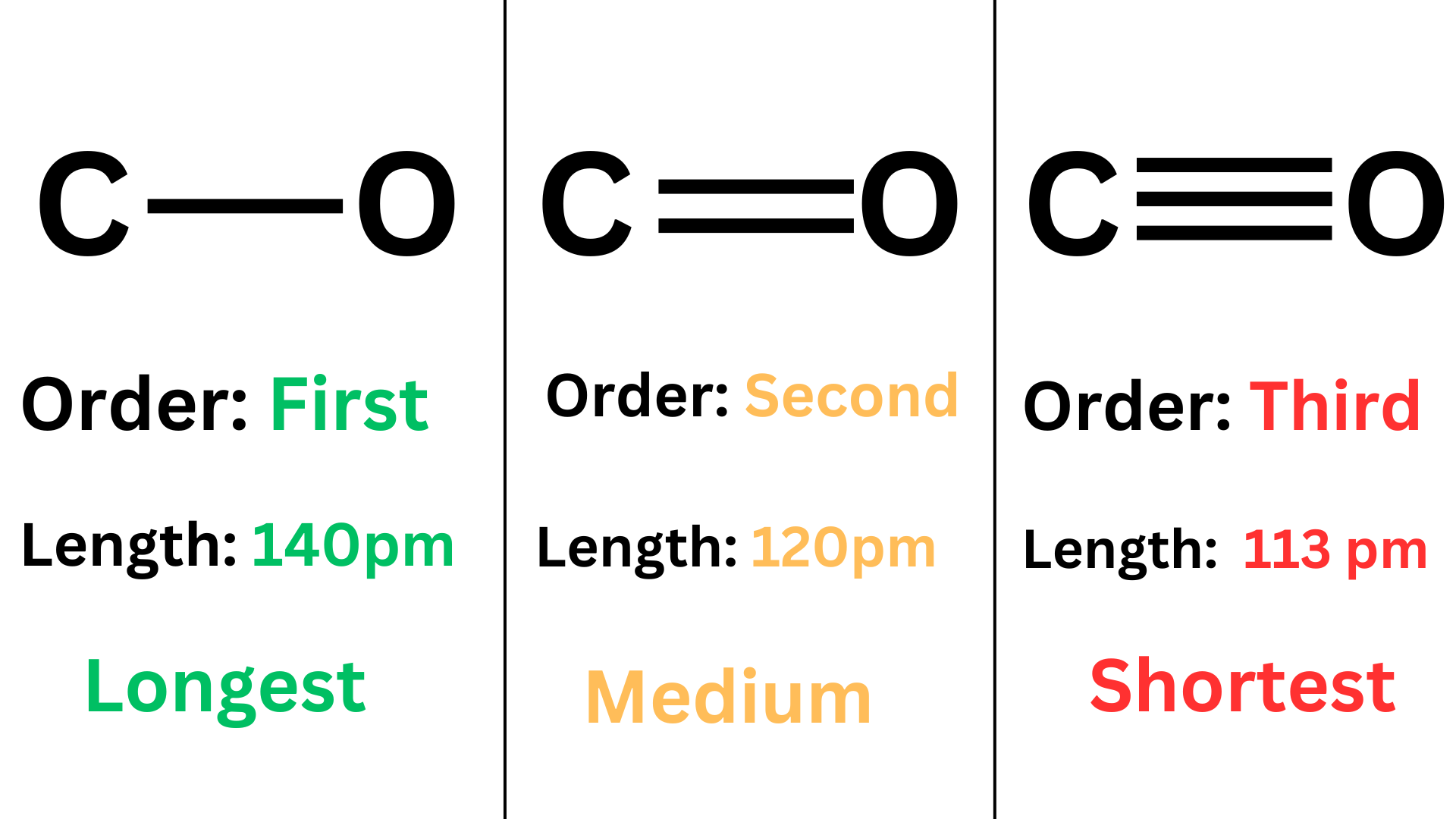

Bond Order: Bond order describes the number of covalent bonds between two atoms. A single bond is a bond order of 1. A double bond is a bond order of 2. A triple bond is a bond order of 3.

Bond order is inversely proportional to bond length. When comparing bonds between the same pair of atoms, a double bond is shorter than a single bond, and a triple bond is shorter than a double bond.

Furthermore, bond order is proportional to bond strength. Between the same pair of atoms, a triple bond is stronger (higher bond energy) than a double bond. A double bond is stronger (higher bond energy) than a single bond.

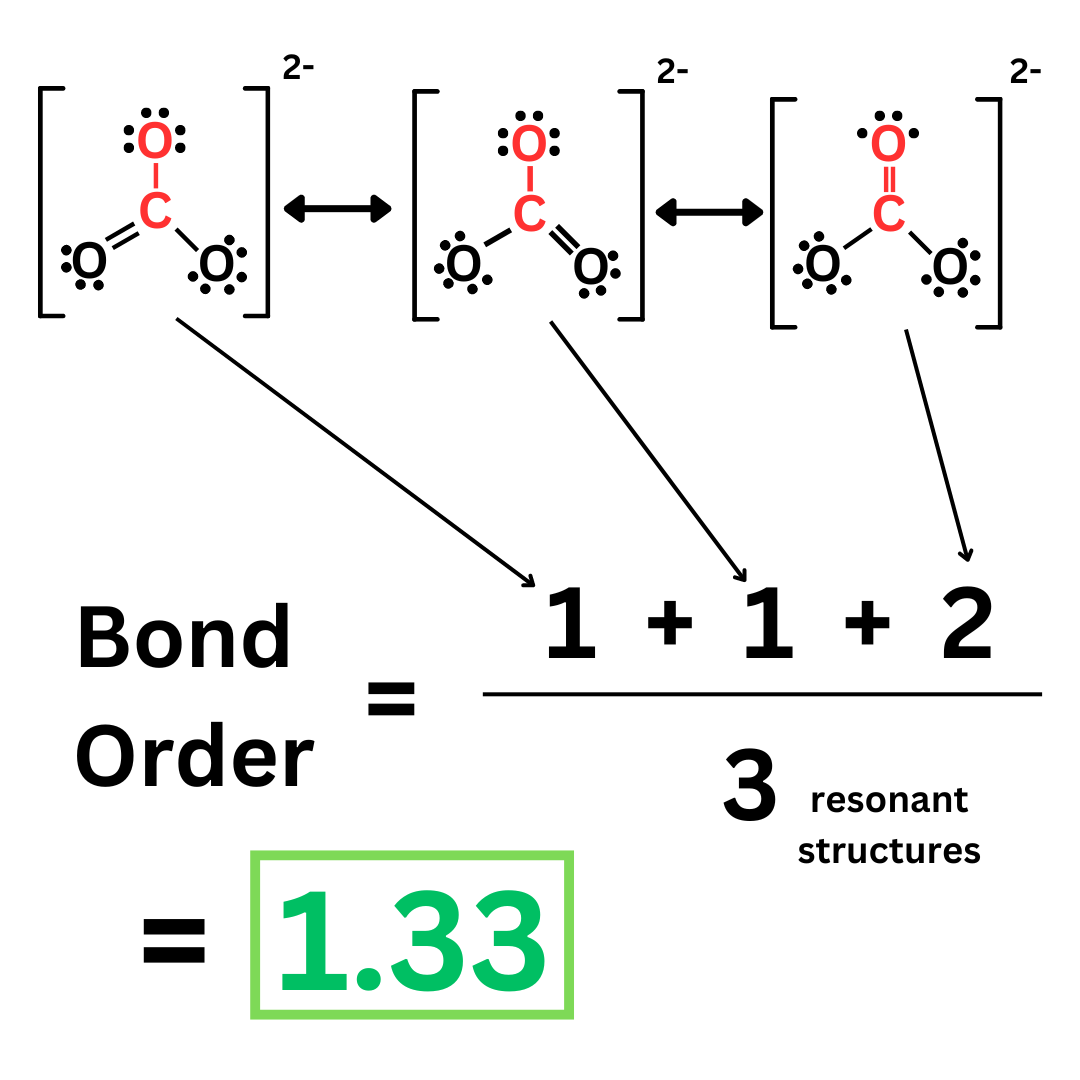

Bond order gets a little bit tricky when it comes to resonance. For molecules with multiple resonant structures, bond orders are not always integers.

Let’s look at carbonate ↴

What is the bond order of the carbon-oxygen bond highlighted in red? Well, it’s different in each resonant structure. In the first two structures, the bond order is 1. But in the third structure, the bond order is 2. The actual bond order is neither.

To find the bond order when dealing with resonance, you have to average the bond orders of the different resonant structures.

So, the bond order of this carbon-oxygen bond is 1.33. This makes sense because it is neither a single nor double bond, rather in between them. Remember, that’s how resonance works: the molecule cannot be represented by one resonant structure, but rather a mixture of all three.

A 1.33 bond order means that this bond is stronger and shorter than a single bond. However, it is weaker and longer than a double bond.