We call these the “minor gas laws” because it’s not important that you actually memorize the names of each one. Moreover, the “Ideal Gas Law” (which you will learn about later) combines most of these laws into one. Still, you should conceptually understand why each one makes sense

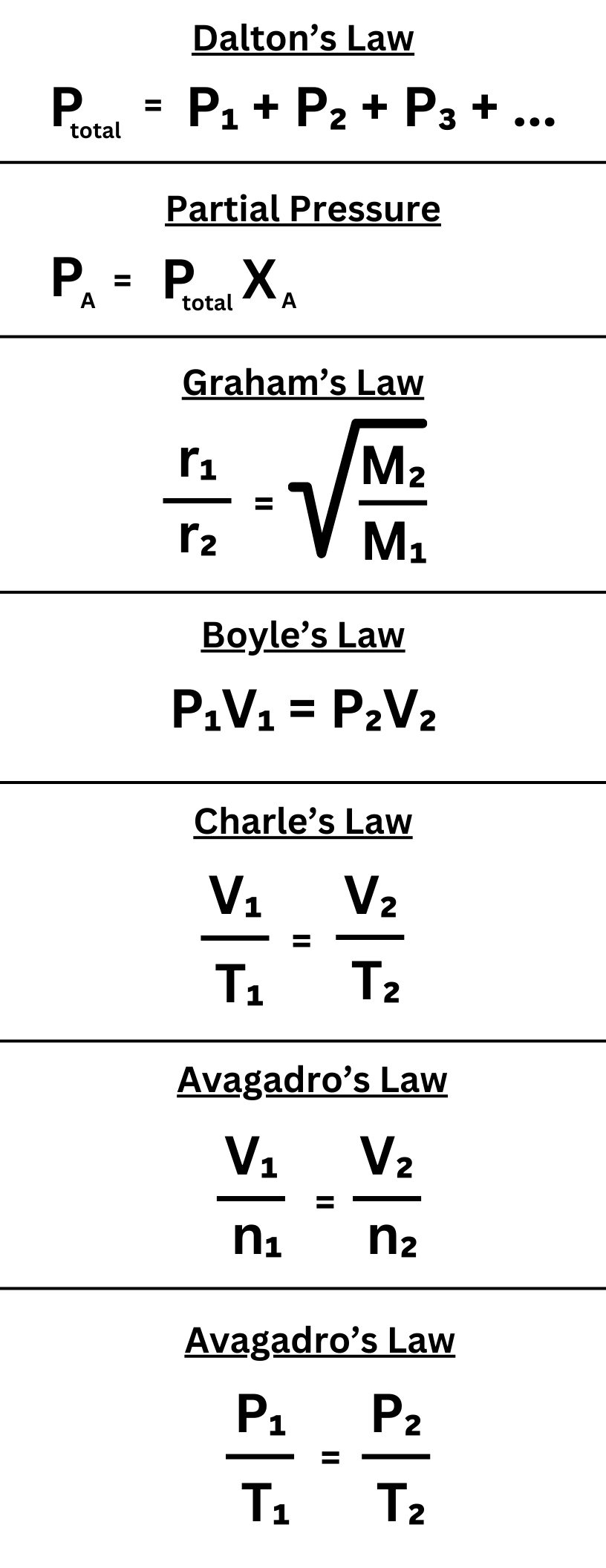

Dalton’s Law

The total pressure exerted by a mixture of gasses is equal to the sum of pressures exerted by each individual gas.

ΣP = P₁ + P₂ + P₃ + P₄ …

The pressure of an individual gas within a mixture of gasses is called its partial pressure.

Example Problem

A container contains oxygen gas with a partial pressure of 1.0 atm, hydrogen gas with a partial pressure of 0.5 atm, and carbon dioxide with a partial pressure of 0.2 atm. To find the total pressure of the mixture of gasses, we add the partial pressures.

Answer

ΣP = 1.0 atm + 0.5 atm + 0.2 atm = 1.7 atm.

To find the partial pressure of a gas, you multiply its mole fraction by the total pressure of the mixture.

Pₐ = Xₐ(Pₜₒₜₐₗ)

– Pₐ is the partial pressure of gas “a”

– Xₐ is the mole fraction of gas “a”

– Pₜₒₜₐₗ is the total pressure of the system

Recall that mole fraction = (moles of component)/(total moles of mixture)

Example Problem #2

There is 1.2 mol of oxygen gas in a mixture of gasses. The pressure of the mixture of gasses is 2.0 atm. There is 1.5 mol of gas in total. Find the partial pressure of oxygen.

Answer

To find the partial pressure of oxygen, we first need to calculate its mole fraction.

X = 1.2 mol oxygen/1.5 mol total = 0.8

Now, multiply that by the total pressure: P = 0.8(2.0 atm) = 1.6 atm

Graham’s Law

Graham’s Law deals with effusion and diffusion.

Diffusion: The process in which particles move from areas of high concentration to low concentration through random motion.

Ex. When you spray perfume into a room, at first you can smell the cloud of perfume because it is initially at a high concentration. The perfume particles collide and overtime spread out. Eventually, you can’t smell it anymore.

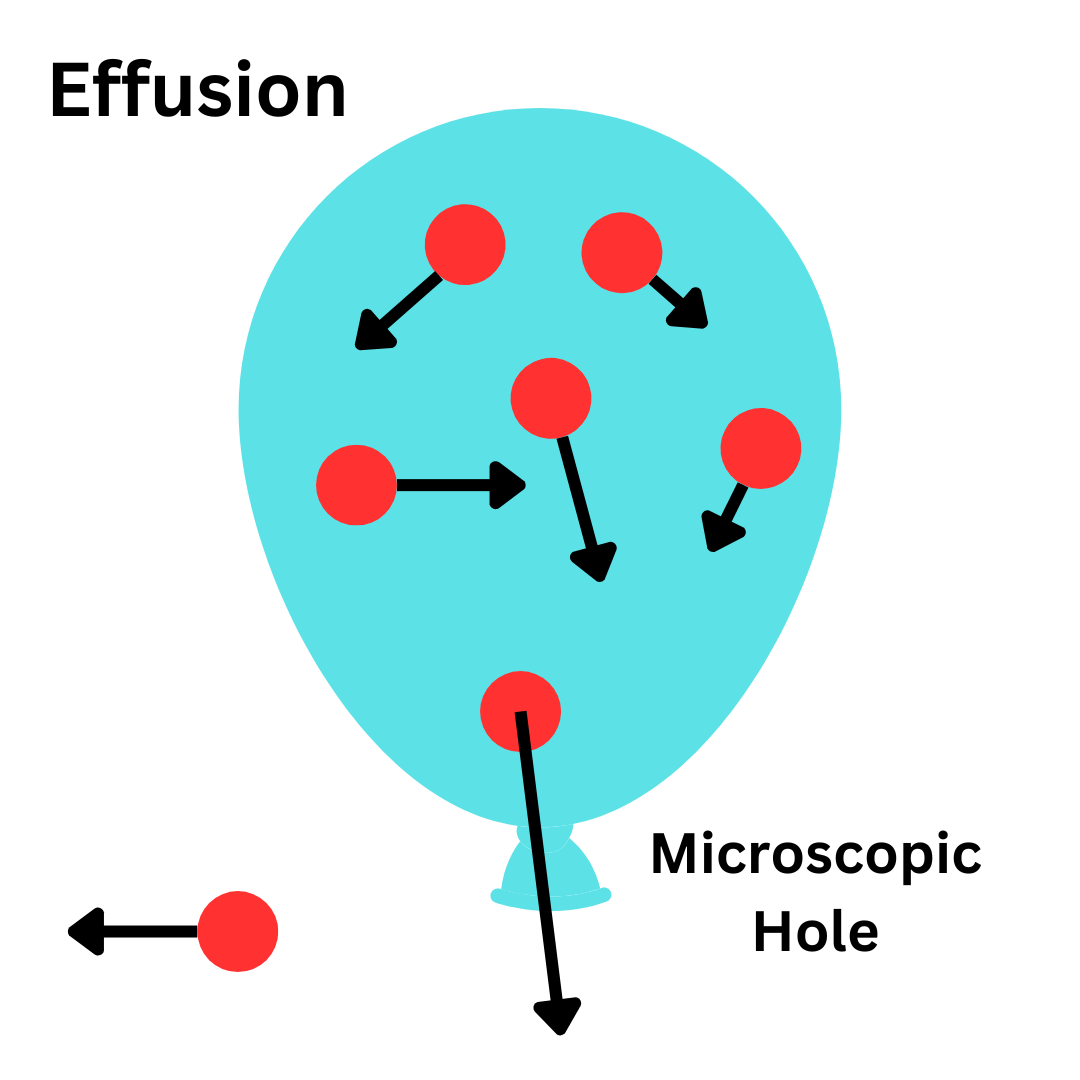

Effusion: The process in which gas molecules escape their container through a microscope hole.

Ex. A balloon filled with air will slowly start to deflate because of effusion. There is a microscopic hole at the bottom of the balloon, allowing gas particles to slowly escape overtime.

Graham’s Law states that the ratio of the rates of effusion of two gasses is inversely proportional to the square root of the ratio of their molar masses.

Mathematically ↴

Therefore, gasses with a higher molar mass effuse slower. Gasses with a lower molar mass effuse faster.

Let’s do two different example problems that you might see related to Graham’s Law:

Example Problem #1

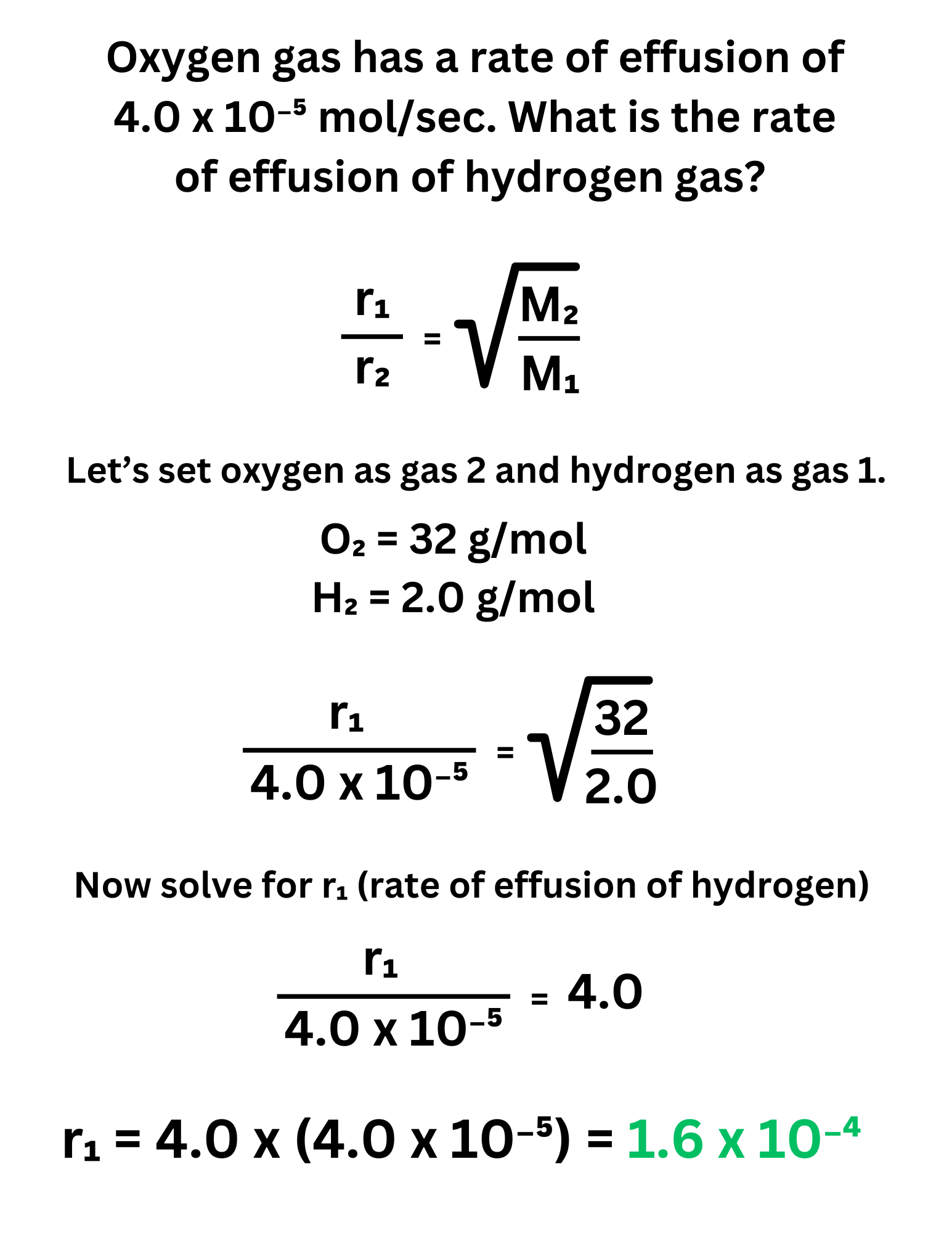

Oxygen gas has a rate of effusion of 4.0 x 10⁻⁵ mol/sec. What is the rate of effusion of hydrogen gas?

Answer

Example Problem #2

Helium has a rate of effusion twice that of another gas. Which of the following gasses could be the other gas?

A. O₂

B. NH₃

C. CH₄

D. CCl₄

Answer

Boyle’s Law

Boyle’s Law, along with the rest of the laws in this topic, will be incorporated into the ideal gas law, but it is still important to understand each of them individually.

Boyle’s Law states that when the temperature and the moles of gas remain constant, pressure is inversely proportional to volume.

Mathematically, pressure multiplied by volume will remain constant.

P₁V₁ = P₂V₂

– Where P₁ and V₁ are the pressure and volume at a point in time

– P₂ and V₂ are the pressure and volume at another point in time

Example Problem #1

A 1.5 L container of gas has a pressure of 1.0 atm. The volume of the container is decreased to 0.75 L. What is the new pressure?

Answer

Graphically, at constant temperature and moles of gas, this is what the relationship between pressure and volume looks like ↴

As you can see, as volume increases, pressure decreases, and vice versa. Think back to what pressure actually is: Pressure = Force/Surface Area. Increasing volume also increases the surface area, which decreases the pressure. Decreasing volume decreases the surface area, which increases the pressure.

Charles’ Law

Charles’ Law states that when the pressure and moles of gas remain constant, volume is directly proportional to temperature.

Mathematically, volume divided by temperature will remain constant.

V₁/T₁ = V₂/T₂

– Where V₁ and T₁ are the volume and temperature at a point in time

– V₂ and T₂ are the volume and temperature at another point in time

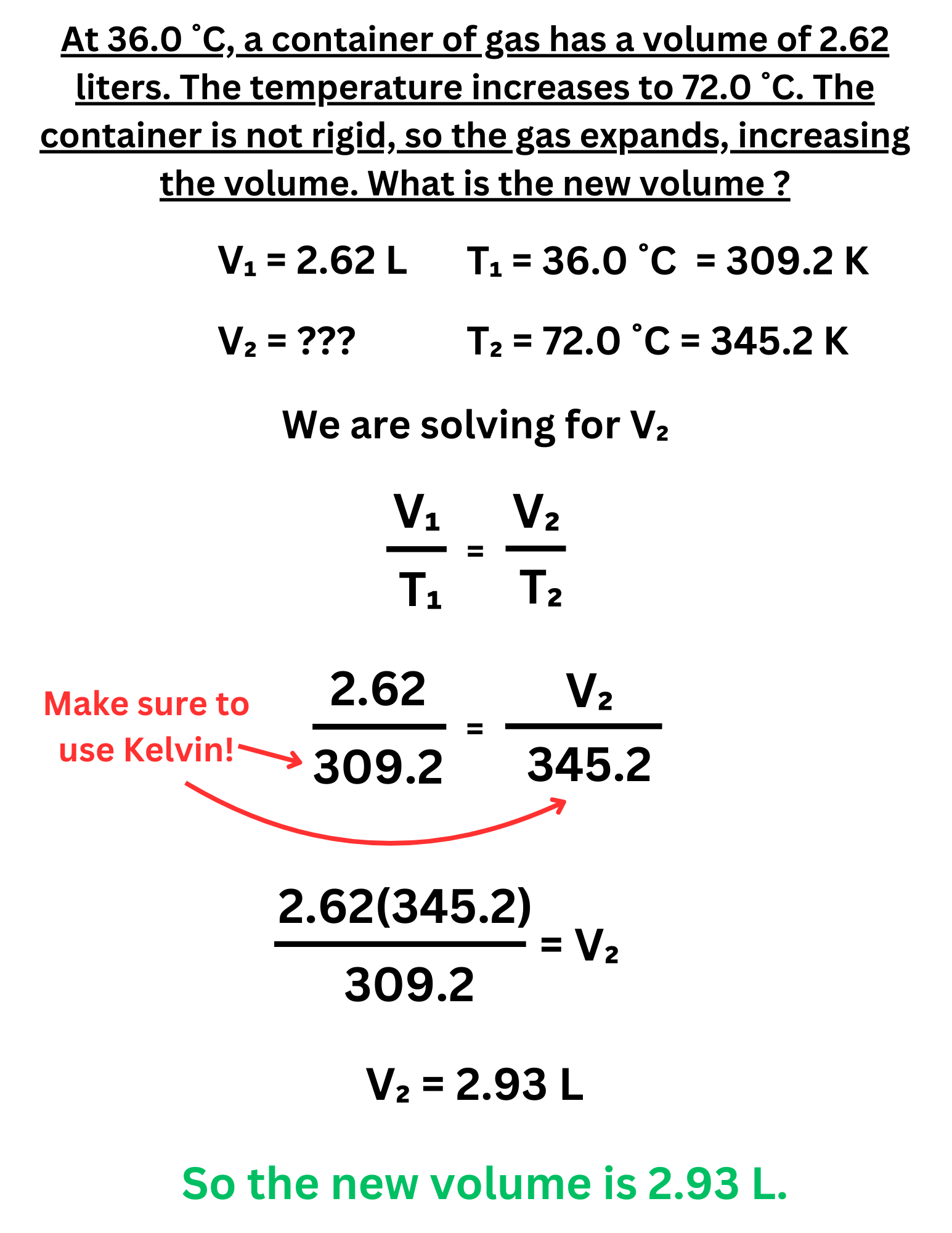

Example Problem

At 36.0 ˚C, a container of gas has a volume of 2.62 liters. The temperature increases to 72.0 ˚C. The container is not rigid, so the gas expands, increasing the volume. What is the new volume ?

Answer

Graphically, at a constant pressure and moles of gas, the relationship between volume and temperature looks like this ↴

As you can see, as temperature increases, so does volume. Remember, this law holds true at a constant pressure. If you increase temperature, the gas molecules gain energy. They therefore collide with the walls of the container with more force.

An increase in force would lead to an increase in pressure. For the pressure to remain constant, the volume would have to increase. This would increase the surface area. Force would increase, but so would surface area, keeping the pressure constant.

Avogadro’s Law

Avogadro’s Law states that when pressure and temperature are constant, volume is proportional to moles of gas.

Mathematically, volume divided by moles is constant.

V₁/n₁ = V₂/n₂

– Where V₁ and n₁ are the volume and moles of gas at one point in time

– V₂ and n₂ are the volume and moles of gas at another point in time

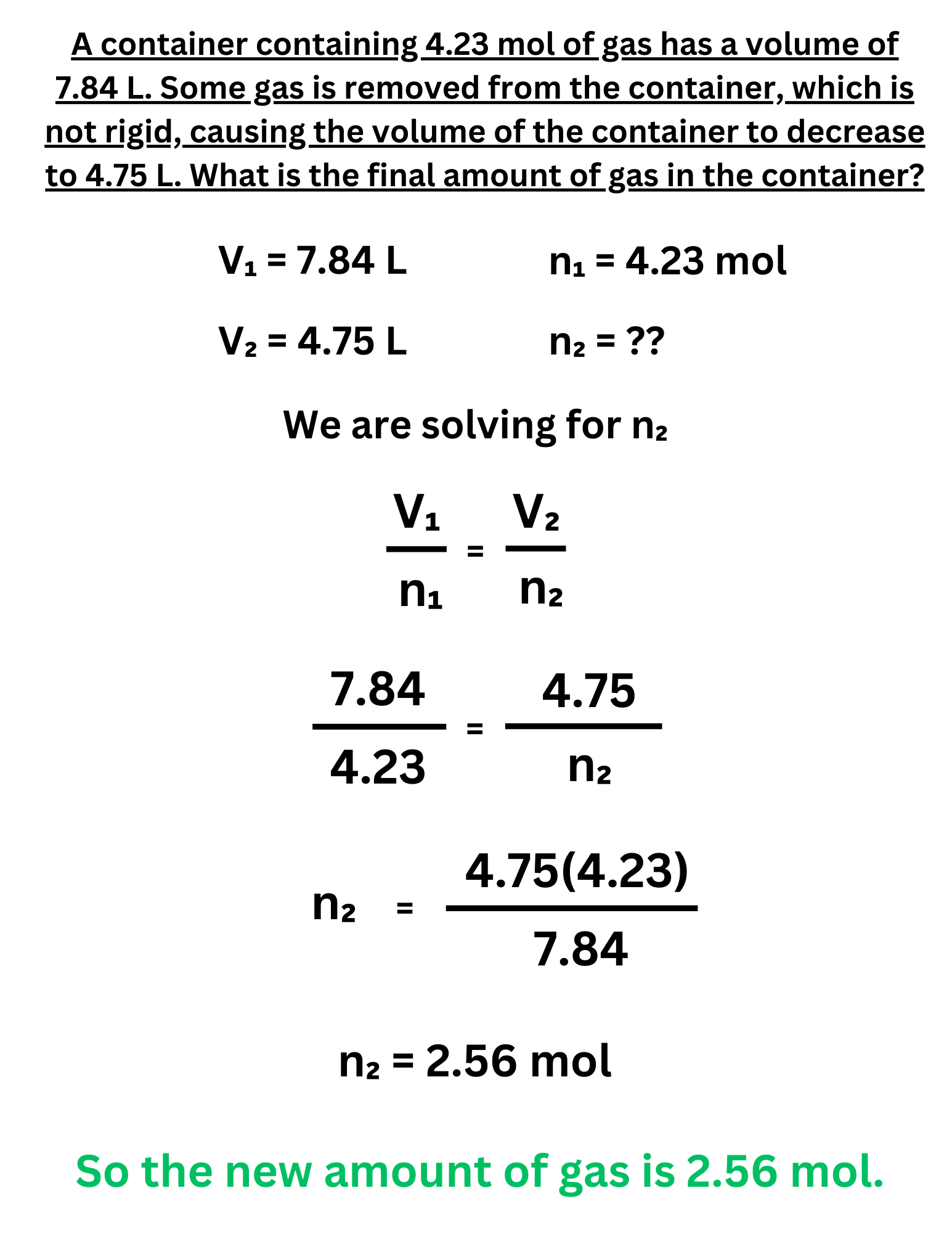

Example Problem

A container containing 4.23 mol of gas has a volume of 7.84 L. Some gas is removed from the container, which is not rigid, causing the volume of the container to decrease to 4.75 L. What is the final amount of gas in the container?

Answer

Graphically, when pressure and temperature are constant, the relationship between moles and volume looks like this ↴

As the moles of gas increase, the volume does too. Remember that this law holds true at a constant temperature. If you add more gas molecules to a container, more collisions will occur with the walls of the container. Thus, the molecules will exert a greater total force. Increasing force would increase the pressure. To keep the pressure constant, the surface area increases via an increase in volume.

Gay-Lussac’s Law

Gay-Lussac’s Law states that when volume and moles of gas remain constant, pressure is proportional to temperature.

Mathematically, this means that pressure divided by temperature is constant.

P₁/T₁ = P₂/T₂

– Where P₁ and T₁ are the pressure and temperature at a point in time

– P₂ and T₂ are the pressure and temperature at another point in time

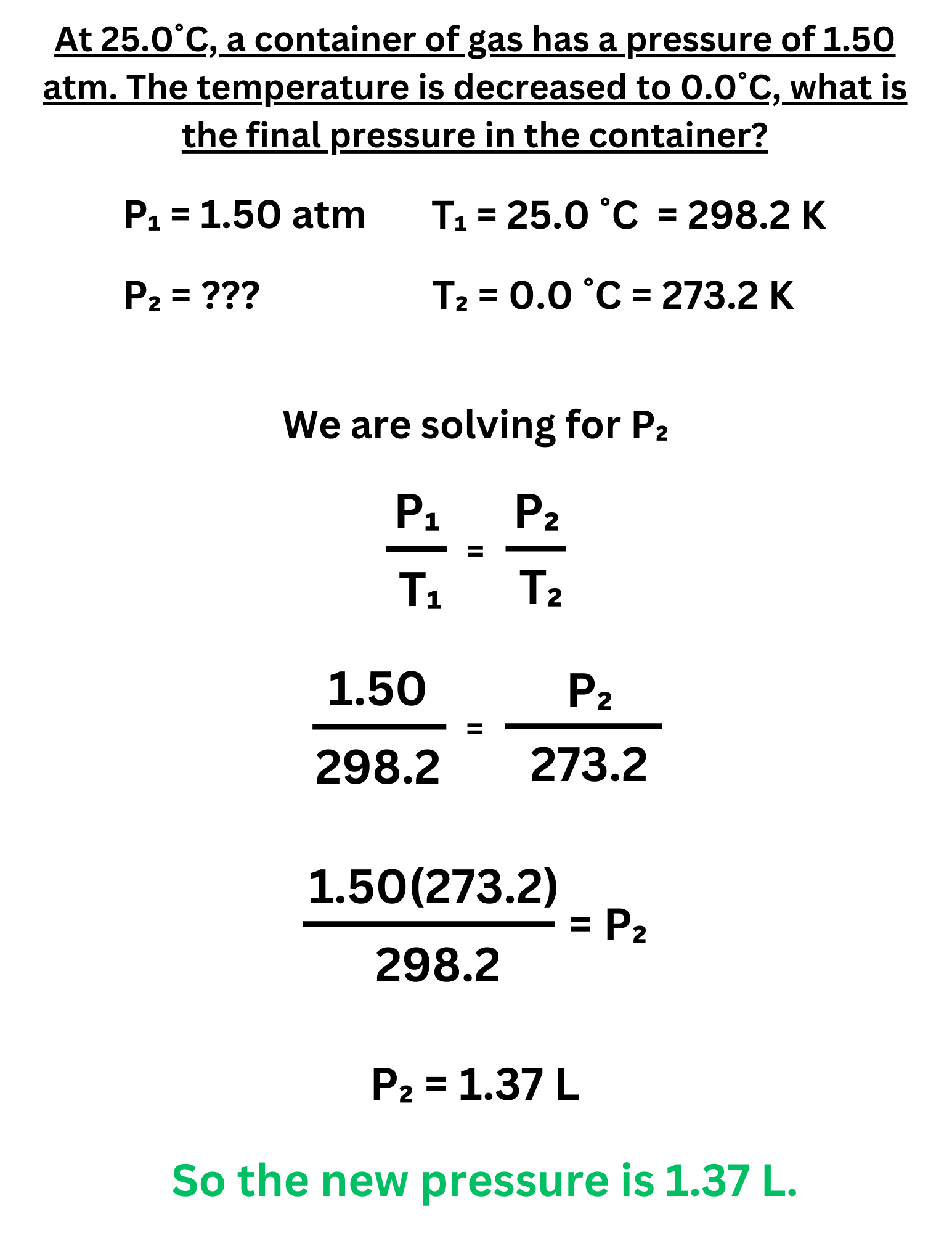

Example Problem

At 25.0˚C, a container of gas has a pressure of 1.50 atm. The temperature is decreased to 0.0˚C, what is the final pressure in the container?

Answer

Graphically, at a constant volume and moles of gas, the relationship between pressure and temperature looks like ↴

An increase in temperature leads to an increase in pressure. As you increase the temperature, the gas molecules gain energy. Consequently, they exert more force on the walls of the container. Pressure = Force/Surface Area, so an increase in force leads to an increase in pressure.

Cheat Sheet

Here is a little “cheat sheet” that summarizes all of the equations in the “Minor Gas Laws” topic.